Stutthof: The Delayed Liberation of the Baltic Nightmare

In the frozen shadow of the Baltic Sea, north of present-day Poland, the name Stutthof remains etched in collective memory as a synonym for horror and inhuman suffering. The first concentration camp established outside the German Reich in September 1939 and one of the last to be liberated, Stutthof embodied the stubborn cruelty of the Nazi regime, which refused to relent even in the final moments of World War II . With the fall of the Third Reich and the approach of Soviet troops, the camp became an open-air purgatory where thousands of prisoners, reduced to living skeletons, struggled for a second breath.

For over five years, Stutthof hosted a mosaic of victims: Jews from Poland and the Baltic states , Polish resistance fighters, German political prisoners, Catholic priests, communist opponents, and even Western Europeans arrested by the Nazi machine. Conditions were brutal: forced labor in the surrounding marshes, chronic hunger, epidemics, and summary executions. The cold, damp Baltic winter often killed those still unscathed by hunger.

In early 1945, as the Red Army crossed the Vistula River and advanced toward East Prussia, Stutthof concentration camp became a death trap. Unwilling to admit defeat, the SS organized death marches to evacuate thousands of prisoners westward. These ghostly columns of exhausted men, women, and children traversed snow-covered roads under the blows of their guards. Many fell and were shot on the spot. Those who remained in Stutthof were abandoned in an environment where hunger and typhus became silent executioners.

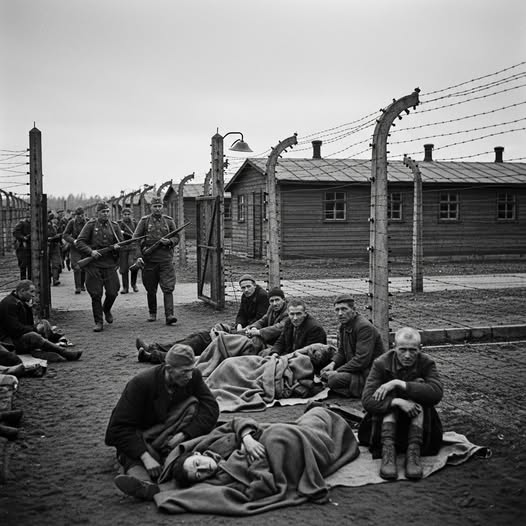

On May 9, 1945 , the day after Germany’s surrender, Soviet troops finally entered the camp. The sight they were met with was one of almost indescribable devastation. The wooden barracks, surrounded by twisted barbed wire, bore the marks of months of neglect and abandonment. The corridors echoed with an eerie silence, broken only by the soft groans of survivors too exhausted to stand. Some crawled on the ground to reach a bit of standing water, others remained motionless, staring at an invisible point, as if they dared not yet believe their ordeal was over.

A Soviet soldier, young and hardened by years of fighting on the Eastern Front, knelt beside a woman wrapped in a tattered blanket. Her emaciated face was ravaged by hunger and disease. She slowly looked up at him and, in a barely audible whisper, whispered, “We thought no one would come.” These simple words contained all the despair of those who thought they had been forgotten, and all the fragile glimmer of hope that the liberation of the camp finally brought .

For Soviet soldiers, hardened by years of atrocities, the sight remained a shock. They saw razed cities, battlefields strewn with corpses, but Stutthof offered them a different face of barbarity: slow, methodically inflicted agony. Many of them, though accustomed to the brutality of war, later admitted that this sight haunted them long after victory.

A typhus epidemic raging in the camp hampered rescue efforts. Military doctors were dispatched to try to save those who could still be saved. However, for many, liberation came too late: hundreds died in the following days, their bodies too weakened to withstand even a sip of water or a piece of bread. The survivors were gradually evacuated to makeshift hospitals and convalescence centers, where a long and painful recovery, both physical and mental, began.

The history of Stutthof is not just about a tragic end. For years, the camp was a central tool of the Nazi policy of extermination and oppression. In total, over 110,000 people were imprisoned there, with estimates ranging from 60,000 to 65,000 victims. Makeshift gas chambers were constructed from railway wagons and enclosed barracks. Executions by hanging or shooting were common, as were medical experiments on prisoners. The camp also served as a transit center for other extermination sites, thus connecting Stutthof to the wider Holocaust network .

After the war, Stutthof became a symbol of Nazi crimes in the eastern territories. Trials of guards and collaborators, held primarily in Gdańsk in 1946-47, helped reveal details of the extermination machine. Some defendants attempted to minimize their role, claiming they were merely executioners. However, the testimony of survivors—men and women who witnessed the deaths of their loved ones firsthand—undermined these fragile defenses. Subsequent verdicts sentenced several officers to death or long prison terms, sending a clear message: even in the final days of the war, crimes committed in a place like Stutthof would not go unpunished.

Today, the Stutthof site has become a museum-memorial , a place of remembrance and education. Visitors can see restored barracks, rusty barbed wire, and monuments dedicated to the victims. Walking across this frozen ground, between rows of wooden barracks, one can feel the weight of history and understand that the freedom enjoyed by current generations came at the cost of untold suffering. Guides remind visitors that this camp was both the first to open its gates under occupation and one of the last to close them—a stark reminder that Nazi ideology stopped at nothing, even on the eve of its fall.

The testimony of a woman whispering, “We thought no one would ever come,” has endured for decades as a universal lesson. It reminds us that behind the numbers—tens of thousands of victims—hide individual stories, faces, and voices. Today’s SEO, combining keywords like Holocaust , concentration camp , Stutthof , or World War II , should never reduce these realities to mere search engine data. These words carry with them memory, truth, and responsibility.

For historians and writers, telling the story of Stutthof means defying oblivion. In a world where survivors are gradually disappearing, the task of conveying their experiences takes on an urgent meaning. The liberation of Stutthof is not just a date on a timeline; it is a belated victory over despair, a confirmation that even in the deepest darkness, a glimmer of humanity can remain.

Visiting Stutthof, one understands that the war did not end for the prisoners with the first cannon shot in May 1945. For them, true liberation was a slow process, marked by invisible wounds, memories of hunger and fear that never faded. Some returned to life in a devastated Europe, others emigrated, forever carrying the burden of what they had seen in silence or in stories.

Stutthof is not just another chapter in the history of the Holocaust. It is a lesson in human resilience and a warning about what can happen when hatred and indifference prevail. The calm, gray Baltic Sea still washes the camp’s neighboring shores, a silent testament to a past we have a duty never to erase. Every year, flowers are laid on the monument’s tombstones, candles are lit, and voices recite prayers or poems. They all say the same thing: we remember. And as long as we remember, Stutthof will remain not only a keyword but a cry of human conscience—a reminder that even in the darkest moments of history, compassion and memory can triumph.