Bread for a Stranger – Dachau, 1945

It was the winter of 1945, one of the last of the war, and also one of the darkest. Dachau, the concentration camp the Nazis had designed as a place of systematic extermination, descended into chaos in the final weeks before liberation. Hunger became a daily occurrence, death a neighbor, and suffering a daily bread. In the midst of this hell, however, a story unfolded, revealing not only the tragedy of the Holocaust, but also the indomitable strength of humanity. “Bread for a Stranger – Dachau, 1945” tells the story of a Polish prisoner whose act of compassion and selflessness has remained etched in the memory of posterity, becoming a symbol of hope in a world deprived of light.

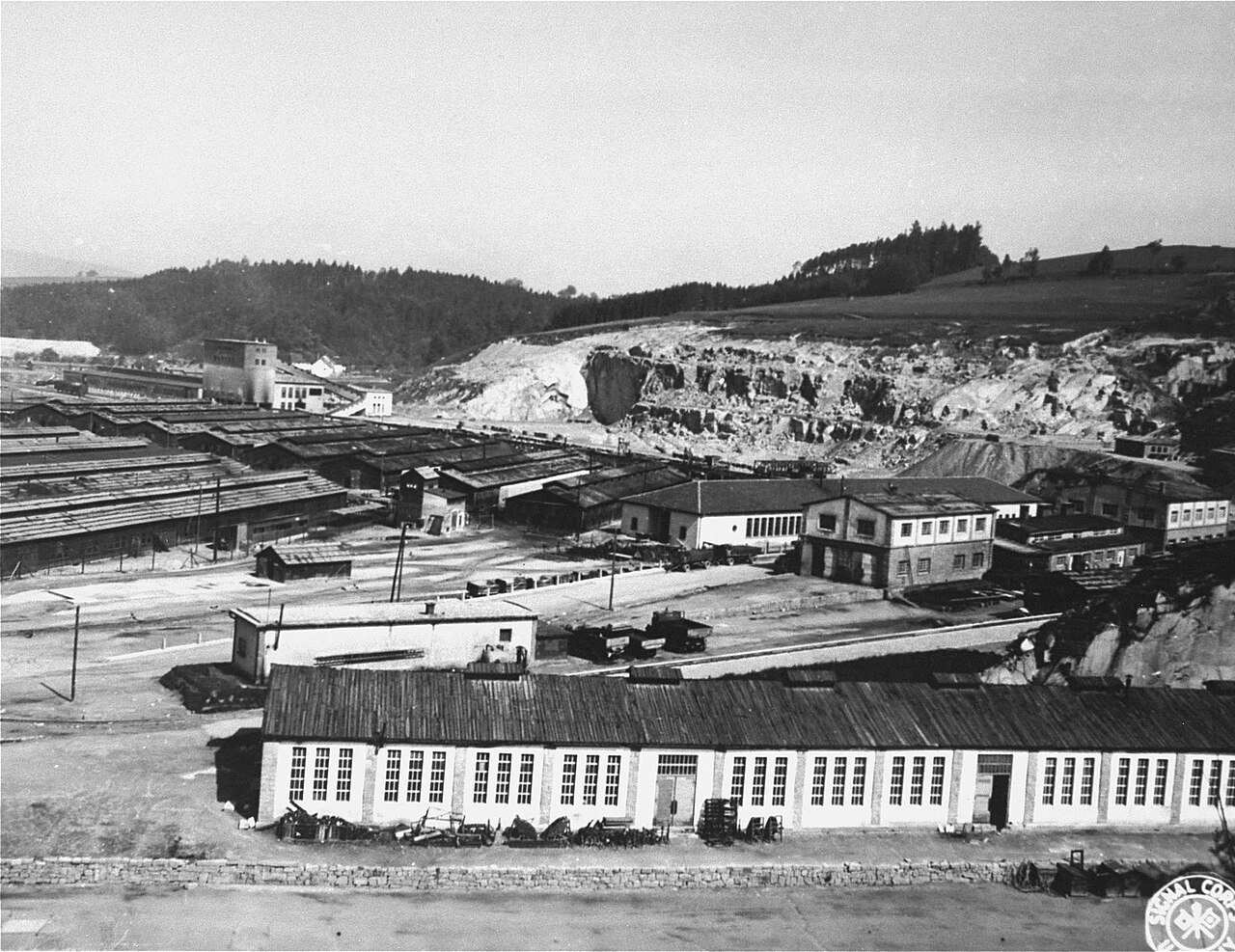

To understand the significance of this gesture, one must imagine Dachau, the first concentration camp established by the Nazi regime in 1933. Initially intended to imprison political opponents, this place quickly became a machine of repression against entire nations, particularly Poles and Jews. By 1945, as the Allied armies approached Bavaria, the camp was overcrowded. Hunger reigned. Daily rations were limited to thin soup and a piece of bread, often moldy or contaminated. Each bite meant life; each crumb could determine the next day’s survival. In such conditions, the instinct for survival generally prevailed over everything else.

It was then that a Polish prisoner, whose name we never learned, made a choice that defied the logic of daily life in the camp. On the verge of exhaustion, he found half-crumbs of bread. It was an opportunity: he could hide them in a corner of his striped uniform, eat them alone, and prolong his life by a few hours or a few days. No one would condemn him, no one would have the right to judge him. Yet, he chose something else.

Instead of hiding the bread, the prisoner approached another man, a stranger whose name he didn’t even know. This stranger was on the brink of life and death. His eyes were sunken, his body emaciated to the bone, and he breathed heavily, as if each breath required a superhuman effort. The Polish prisoner knelt beside him and held out his hand. He offered the half-crusted loaves of bread—which, in Dachau, were like gold, currency, the very meaning of survival—to the stranger. Discreetly, without witnesses, without expecting gratitude. It was neither a transaction nor a survival strategy. It was pure, selfless empathy.

This simple gesture became proof that even in hell, a small piece of paradise could be found. In a world designed to destroy bonds and annihilate humanity, a moment arrived that changed everything. Offering bread to a stranger was more than just a piece of food. It was an act of rebellion against the logic of hatred and destruction. It was proof that the human spirit, however fragile, can withstand the greatest darkness.

The stranger survived only one more night. The next morning, his body was already cold, but a small note was found on him. It is unknown where he obtained this paper or what he wrote it on; perhaps it was a scrap of paper he had long hidden, perhaps acquired by chance. On this note were words of promise: if he survived, he would tell the story of the man who shared the bread. It was a final gesture of gratitude, a testament that kindness does not die with the body. Though dead, the stranger left behind a testimony that became a bridge between the past and the future.

The camp archives did not allow for the identification of the donor. Only the words “A good man” were inscribed. This anonymity, instead of oblivion, became immortality. “A good man”—so simple and yet so powerful—captured the very essence of human dignity.

The story of “Bread for a Stranger” is not simply a camp episode. It reminds us of the power of empathy, capable of surviving where everything else was stolen: family, name, freedom, hope. At Dachau, hunger was an instrument of torture. It was easier to break, subdue, and strip starving people of all resistance. And yet, it was precisely in the face of this hunger that an act occurred, shattering the mechanisms of hatred.

In a time when only bread mattered—that dry, hard, and often moldy piece of bread—the Polish prisoner demonstrated that values like compassion and solidarity transcend the laws of biological survival. This message is relevant not only to the history of the Holocaust but also to the present. It shows that in the darkest conditions, where a person is reduced to a number and a source of labor, the very act of selflessness becomes the greatest victory.

The Dachau concentration camp was liberated on April 29, 1945, by the 42nd U.S. Infantry Division. The soldiers who entered were shocked by the extent of the suffering they witnessed: thousands of emaciated figures, piles of corpses, and the stench of death hanging in the air. But alongside this image of death, stories like this one—the story of bread shared with a stranger—survived. For many survivors, these accounts were a glimmer of hope, proof that, despite all the obstacles, it was worthwhile to believe in humanity.

The Polish prisoner, whose name we will never know, left behind a legacy greater than any tangible memory. His act was recorded in the memories of his fellow prisoners, and later in documents and memoirs. Thanks to this, we can remember this story today not only as a fact, but also as a symbol—a symbol of humanity in a time when humanity was thought to be annihilated.

The story of “The Man from Dachau” reminds us that the memory of the Holocaust is not merely a catalog of crimes, but also a space for narratives of courage and empathy. Historical research shows that such acts were rare. The concentration camp aimed to stifle compassion, to impose the principle of “every man for himself.” Yet even individual acts of kindness possessed a power that transcended time and space.

This narrative is therefore an important element of Holocaust education. It shows younger generations that, in the face of totalitarian scourge, it was possible to remain human. It teaches that history is not only the story of victims and perpetrators, but also the story of everyday heroes – anonymous, nameless, yet eternal through their example.

When we talk today about Dachau, Auschwitz, Majdanek, or Treblinka, we often focus on statistics, the number of victims, and the camp structures. While this is necessary for a comprehensive understanding, individual stories are just as important. They make history vivid, relatable, and understandable. This “good man” had no name, but he did something that will be remembered. Paradoxically, his anonymity is his strength: everyone can see themselves in him, everyone can read this story as a call to everyday empathy.

Because while the world has changed since 1945, there are still places where people suffer, are persecuted, and lack food. Situations still arise where one must choose between selfishness and solidarity. The story of the “Man of Dachau” reminds us that a choice is always possible, even where there seems to be no hope.

“Bread for a Stranger – Dachau, 1945” tells the story of a simple gesture that became a symbol. In a place designed to destroy humanity, a Polish prisoner chose compassion over survival. He shared bread with a dying stranger, and his act was preserved through a note, archives, and memories. He was called “the good man”—and that name became his immortality.

This is a story that reminds us that even in the darkest corners of history, sparks of good have existed. That empathy can survive where everything else is destroyed. And that remembering such acts is our responsibility, so that the future never forgets that humanity has the power to triumph over evil.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creative reasons and suitability for historical illustration purposes.