The Stone Oath: Gross-Rosen, February 1945

In February 1945, the plains of Central Europe were covered in a thick blanket of snow, as if nature had sought to hide, beneath its icy veil, the scars left by war. But some wounds never heal. In the heart of Silesia, behind the barbed wire and watchtowers of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, the snow was only a shroud over the horror. Here, the cold erased nothing: it accentuated the protruding bones, bit into the flesh already devoured by hunger, and froze the tears of the survivors.

This camp, sinister among many others, was known for its granite quarries. Every stone wrested from the mountain had been excavated at the cost of the prisoners’ blood and flesh. Men, women, and sometimes children, were reduced to tools, slaves to the stone and Nazi madness. Forced labor was not just a task, but a deferred death sentence. Arms broke under the weight, lungs were exhausted in the dust, backs bent until they broke. It was said that Gross-Rosen devoured its prisoners faster than any other camp: the quarry was an insatiable monster.

Among the thousands of souls imprisoned there was a stonemason, a craftsman once proud of his craftsmanship. Before the war, he carved church steps, public monuments, and grave markers for his loved ones. His was a noble profession, linked to memory and permanence. But at Gross-Rosen, his mastery of stone became his condemnation. The Nazis saw him not as a man but as an instrument: his hands, which once shaped beauty, were reduced to carving rock at a hellish pace.

Year after year, he struck, sawed, lifted, until his body was nothing more than a shadow. His muscles melted, his ribs became visible like the edges of an eroded quarry. Each blow of the hammer, each chip of granite tore away a piece of his humanity. And yet, he held on. Perhaps thanks to his comrades, perhaps thanks to the fragile flame of hope, or simply because he wanted, one day, to see a sky without barbed wire again.

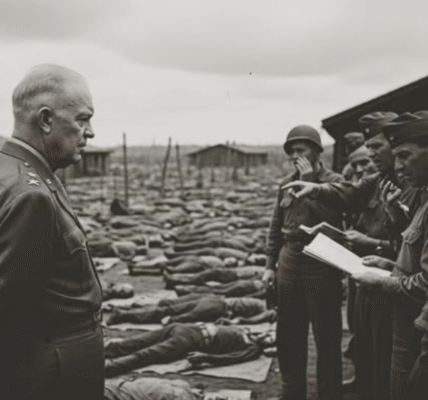

On February 13, 1945, the Red Army tanks approached. The front was advancing, and with it the hope of deliverance. The panicked SS guards began to evacuate the camp, taking thousands of prisoners with them on the terrible “death marches.” But some remained, too weak to walk. Among them was our stonemason. He no longer had the strength to stand. His body, ravaged by deprivation, refused to obey.

It was his comrades who carried him, a frail body supported by four pairs of arms, like a living cross they refused to abandon. Together, they crossed the snow, passed through the gates of the camp, where the silhouettes of Soviet soldiers appeared in the icy mist. The liberating prisoners were themselves struck by what they discovered: beings reduced to the state of specters, but whose eyes, despite everything, still shone with an irreducible flame.

When the stonemason saw the red uniforms, he understood. Hell had an end.

Too weak to speak at length, he bent down and picked up a small pebble that had fallen into the snow. His fingers trembled, but he clutched it as one clutches a treasure. And in a hoarse, almost inaudible voice, he said:

—I will never be ordered to cut stone again.

This seemingly insignificant gesture was a silent cry more powerful than any speech. For years, every stone raised had been an instrument of servitude. That day, the stone became a symbol once again, not of oppression but of newfound freedom. It was no longer the tool of his slavery, but the tangible proof that he could choose. This simple pebble became an oath, an act of revolt and rebirth.

For those present, this scene remained etched forever. Skeletal men, dressed in rags, surrounding one of their own who, with a gesture, transformed a pebble into an invisible flag of dignity. Years later, witnesses recounted this story in court cases, in museums, in schools. The stone was displayed in some memorial exhibitions as a sacred object, not for its material value, but for what it represented: the victory of human will over planned destruction.

Even today, when you visit the Gross-Rosen Memorial, you can feel that heavy silence, as if the walls and hills echoed that oath. The granite blocks, frozen in their mass, seem to tell of past suffering, but also of a single man’s silent act of rebellion.

Gross-Rosen was not only a place of forced labor, but a link in the industrial chain of death established by the Nazis. More than 120,000 prisoners were deported there; nearly half did not return. The quarry was not the only torture: hunger, disease, beatings, and summary executions were part of daily life. Yet, amid this machinery of annihilation, there were gestures of solidarity: a piece of bread shared, a coat lent, a word whispered at night. These gestures, tiny but immense, saved as many souls as lives.

The Stone Oath belongs to this memory. It reminds us that even broken, a man can still assert his dignity. Even reduced to a breath, he can utter words that resonate across generations.

After the war, the stonemason survived. He never returned to his trade, for every stone reminded him of hell. But he always kept, in a small box, the pebble he picked up that February day in 1945. He told his children, and later his grandchildren, the story. He showed them the stone as one would show them a sacred relic, and said:

— Remember. It wasn’t the stone that destroyed me, it was the hatred of men. But that pebble gave me back my freedom.

Thanks to this testimony, Gross-Rosen’s memory remains alive. It is passed down from generation to generation, as a warning and a lesson.

The story of this prisoner of Gross-Rosen, a stonemason who became a bearer of memory, illustrates how the simplest gestures can have universal significance. To pick up a stone in the snow, to refuse to let it once again be an instrument of enslavement, was to defy Nazi ideology in its most destructive aspect: its desire to erase all dignity.

Today, as the last witnesses disappear, it is up to us to uphold this oath. To remember that in the concentration camps, in the midst of the Holocaust, there were men who, even at the end of their tether, refused to give in.

Gross-Rosen remains a symbol: one of extreme suffering, but also of inner resistance. The stone oath, pronounced in February 1945, still resonates: never again.