The Man Who Tried to Get Up – Poland, 1945

The spring morning fog still hung heavy over the camp’s barbed wire when a new sound pierced the silence-filled air: the roar of Allied tanks. For those surviving behind those barbed fences, every sound carried the weight of a potential miracle. Yet, after so many illusions, no one dared truly believe it. Winter had stolen everything: strength, flesh, faces. But that morning, in Poland, in a concentration camp where death had learned to walk in the open, a figure emerged from the dust.

He was only a shadow, a skeleton dressed in the prisoners’ striped uniform. His ribs protruded like the bars of the cage in which he was imprisoned, and his hands trembled with fever and weakness. Yet, when he saw the strange soldiers beyond the barbed wire, he understood the meaning of duty. Deep in his memory, buried under the weight of hunger and fear, the gesture of his ancestors endured: rising to welcome a guest. Even in the hell of the Nazi camps, hospitality, that simplest and most universal human dignity, still endured.

Then he placed his hands on the dry earth, leaned on his knees, and tried to straighten his body, now reduced to a mere ruin. Every movement was torture, every breath a wrench. But he advanced, step by step, staggering as if the air itself weighed more than the world. And as he collapsed, his mouth half open, he muttered in a broken voice:

—Excuse me … I should get up to greet the guests.

The soldier who rushed to pick him up would never forget that moment. He had seen battlefields, thousands of fallen, but never had he seen such an outpouring of dignity in a broken body. He carried with him not just a man, but a living reminder of what the camps had sought to destroy: humanity.

Many words recur constantly in accounts of the Second World War: horror, barbarity, extermination. But sometimes it’s the smallest gestures that tell the story most faithfully. This prisoner of war in Poland in 1945, anonymous among Holocaust survivors, embodies what it meant to resist in concentration camps. Not brandishing a weapon, but preserving a gesture, a word, a shred of dignity in a world where everything was designed to reduce man to mere existence.

The Nazis built their camps to erase the individual. Prisoners were little more than numbers tattooed on their skin, silhouettes in striped uniforms, crammed into teeming barracks. Hunger was so intense that many could no longer speak, and thirst, when water was scarce, forced some to lick raindrops from the ground. In this context, the desire to stand face to face with a guest was not a simple reflex of courtesy: it was a self-affirmation, a definitive protest against dehumanization.

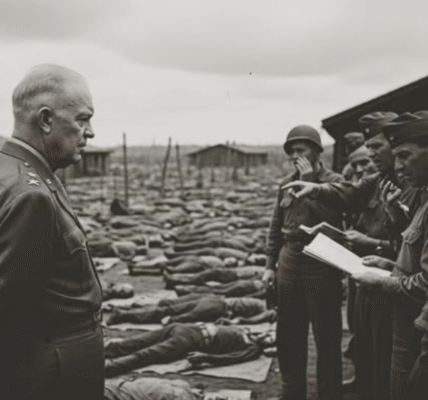

The American soldier—for it was the American army, after crossing the Vistula and Germany, that participated in the liberation of numerous concentration camps in Poland and Germany—later said that that look never left him. It wasn’t fear, nor pain, what he saw in the prisoner’s eyes, but a sort of silent respect, a silent appeal to recognize the value of humanity despite everything.

This man’s story is similar to that of many others. In 1945, the liberation of the camps in Poland—Majdanek, Auschwitz, Stutthof—revealed to the world the true meaning of the word “genocide.” Soldiers entering these territories discovered thousands of emaciated survivors, but also mountains of corpses, open-air mass graves, and barracks filled with disease and despair. Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Buchenwald in Germany—they all offered the same nightmarish vision. Yet, amid these human ruins, life persisted.

The man struggling to get up could have been Jewish, perhaps a Polish resistance fighter, perhaps a Roma, or perhaps simply a civilian trapped in the machine of terror. We will never know his name. But in his struggle to hold his head high, he represented all those who, on the brink of collapse, refused to surrender their dignity. His trembling voice, begging forgiveness for not being able to honor his guests, resonates like a poem more powerful than any political speech.

To understand the power of this gesture, we must contextualize this story. In Poland, starting in 1939, after the Nazi invasion, the number of camps increased. Auschwitz became the center of the system, a symbol of the systematic extermination of European Jews. But around it existed dozens of other camps and subcamps, where millions of men and women were imprisoned. Living conditions were inhumane: hunger, forced labor, disease. In this closed world, every day was a struggle for survival.

The camp where this man was held had no name, but it resembled many others. Electrified barbed wire surrounded the wooden barracks. Guards stood on watchtowers, monitoring the slightest movement. The ground turned to mud in the winter and dust in the summer. The prisoners wore the same striped uniforms, reduced to wandering ghosts. When the liberators arrived, many no longer had the strength to rise from their bunks. Others, driven by an unbridled instinct, tried to do so anyway.

The man collapsed after two steps. But those two steps concealed an entire world: a world of old-fashioned courtesy, a world of respect shown despite hunger, a world of people who, despite blows and humiliations, remained human.

Even today, visiting the monuments erected on the ruins of the concentration camps, it’s difficult to grasp the magnitude of the events. The numbers—six million Jews murdered, hundreds of thousands of resistance fighters, political prisoners, Roma, deportees—offer a sense of urgency, but they speak volumes about individual suffering. It’s stories like this man’s that make memory tangible. Because behind every statistic lies a face, a voice, a gesture.

The importance of visual testimony is crucial. Photographs taken in 1945 by Allied soldiers show emaciated bodies, gaunt faces, and eyes wide with hunger. But they also show survivors struggling to get back on their feet, greeting their liberators with tears, smiles, and, sometimes, a simple whisper: “Forgive me…” It is in these fleeting moments that history is conveyed.

In an age where there’s so much talk about SEO, search, and visibility, it’s important to remember that the most valuable keywords aren’t those that generate profits, but those that perpetuate memory: concentration camp , Holocaust , liberation of Poland , human dignity , World War II . These words, when included in the text, not only optimize search performance, but above all, pay homage to those who can no longer speak.

Because writing about the Holocaust isn’t just about recounting a past tragedy. It’s about anticipating the future. Every time we describe a prisoner struggling to stand despite hunger, every time we tell of a woman clutching an empty bowl like a relic of hope, we defy oblivion with the power of memory.

The American soldier who gathered the fallen man into his arms later recounted feeling the terrifying lightness of his body, almost weightless. He added, however, that he had never carried such a heavy burden: the burden of bearing witness. In the spring of 1945, the world was discovering not only the enormity of the crime, but also the moral obligation to never forget it.

This man may not have survived his wounds, perhaps dying within hours of his liberation, like so many others too weakened to experience freedom. But his gesture endured. It was passed down by word of mouth, from generation to generation, as a universal lesson: humanity may falter, but as long as one person tries to rise again and welcome another, it is not entirely lost.

Today, when we say the words ” Poland 1945 ,” we think of the ruins, the cemeteries, and the columns of survivors staggering toward life. But we should also think of this prisoner who wanted to pay homage to his liberators. His story reminds us that dignity is not measured by physical strength, but by the will to remain human, even when all adversity conspires to silence us.

And though his name has faded from memory, his gesture remains. In that camp, lost in the heart of Poland, in that spring of liberation, a man tried to get up. He couldn’t walk, but he managed to convey to us what it means to live: to stand, even for just a moment, before another person and tell them—in a single breath—that we are still here.