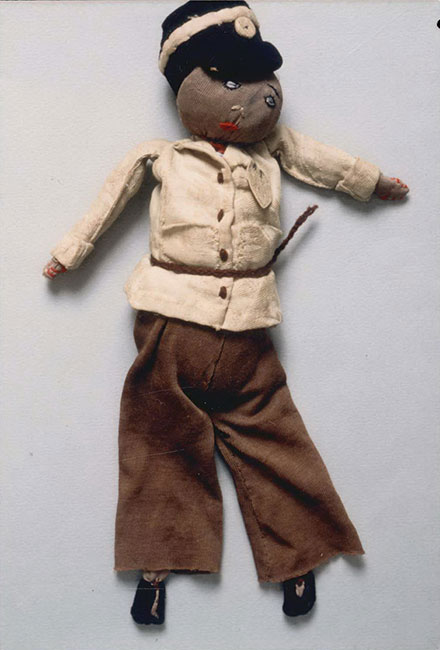

The Waiting Doll – Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia, 1944

In the silence of a freezing afternoon in 1944, in the heart of the Theresienstadt concentration camp, a little girl walked along the line of deportees. Her name was Anka, she was six years old. Her cheeks were still plump despite the hunger that raged everywhere, and her eyes reflected an innocence that nothing, not even the brutality of war, could yet extinguish. In her arms, she clutched a simple rag doll, her only treasure, her only link to the world before, the world of lullabies and family laughter.

When the line stopped, a Red Cross nurse knelt before her. Time seemed to stand still, as if the entire universe were holding its breath. Anka held her doll out to the young woman in the white coat. “Hold it for me, until I come back,” she whispered in a soft, almost trusting voice. The child’s small hand loosened, allowing the object to pass into the adult’s. It was a tiny gesture, but one of overwhelming intensity: an act of trust, a promise for the future.

That day, Anka boarded the train to Auschwitz. She never returned. Like so many other Jewish children, she was gassed upon arrival, snatched from her life before she could even comprehend what was happening to her. The doll, however, remained behind, a silent witness to this final separation.

To understand the scope of this story, we must return to the reality of Theresienstadt, the camp that, according to Nazi propaganda, served as a “model colony” for Jews. In truth, it was a gigantic prison, a transit point where more than 140,000 Jews were interned, before most were sent to Auschwitz or Treblinka. Living conditions there were inhumane: overcrowding, hunger, disease, and constant fear.

But Theresienstadt had one peculiarity: it served as a showcase to deceive the outside world. It was here that the 1944 propaganda film “The Führer Offers a City to the Jews” was filmed , intended to convince the International Red Cross that the prisoners were living in humane conditions. Behind the repainted facades and the fake scenes of happiness, the truth remained the same: for children like Anka, Theresienstadt was nothing more than a waiting room before death.

The doll entrusted to the nurse became much more than an abandoned toy. It represented the silent cry of all those missing children, the material embodiment of a stolen future. In a world where everything was confiscated—clothes, names, lives—the doll was miraculously saved. It survived where so many human beings were reduced to ashes.

When the Allies liberated Europe and museums began collecting artifacts to bear witness to the Holocaust, this doll found its place behind glass. A label read: “Belonged to Anka L., 6 years old. Gassed at Auschwitz upon arrival.” Before this simple text, entire generations of visitors stopped, shocked. For this was no longer just one anonymous story among millions, but the real-life fate of a child and her toy.

Anka’s doll thus became a universal symbol: one of innocence betrayed, but also of memory preserved. It reminds us that behind every number of the Holocaust, there was a name, a face, a child’s voice.

Anka’s story is not unique. Nearly 1.5 million Jewish children were exterminated during the Holocaust. Their childhood was stolen, their laughter stifled. Some, as in Theresienstadt, lived a few months in a semblance of normalcy before being sent to the gas chambers. Others were murdered upon arrival.

In Holocaust museums—at the Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem , the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris —objects similar to Anka’s doll are on display: toys, tiny shoes, children’s drawings. Each tells a story that the executioners wanted to erase.

Today, Anka’s doll is more than an object: it is a bridge between the past and the present. Thousands of visitors shed tears before it. They cry not only for a little girl who disappeared in 1944, but for that broken promise, for that “I will return” that never found an echo.

In a world where witnesses to the Second World War are gradually disappearing, objects become guardians of memory. They remind future generations that the Holocaust is not an abstraction, but a reality made up of lives interrupted, families destroyed, and promises shattered.

What makes the doll’s story so poignant is that it embodies the power of detail in historical memory. Faced with the millions of victims of the Holocaust, we sometimes risk losing ourselves in the abstraction of numbers. But the story of a little girl, her gesture, and her toy, directly touches the human heart.

This is why individual stories are so valuable in telling the story of the Holocaust. They remind us that each victim was a unique individual, with their own dreams, fears, and simple joys. By preserving these stories, we resist oblivion and honor human dignity in the face of barbarity.

While the contemporary world is still marked by wars, forced displacement and violence against innocent populations, Anka’s doll continues to deliver a universal message: that of the absolute necessity of protecting children, of preserving innocence, of rejecting hatred.

Remembering the Holocaust is not only a duty to the dead, but also a warning to the living. Contemplating this doll behind its glass, everyone is invited to reflect: what are we doing today to prevent history from repeating itself?

Anka never returned for her doll. But, in a way, the promise made that day was not broken. The doll waited, patiently, silently. She became a motionless witness that continues to tell, from generation to generation, the story of a little girl and the million and a half children who, like her, were murdered because they were born Jewish.

As a writer, as a European, as a human being, I believe our responsibility is clear: we must continue to tell the story, again and again. As long as words, books, museums, and hearts remember Anka and her doll, she will not have completely disappeared. Her voice still whispers: “Keep her for me, until I come back.” And thanks to collective memory, thanks to our refusal to forget, this doll will wait forever, reminding humanity that every life matters, that every child deserves to live, and that the Holocaust must remain etched as one of history’s darkest lessons.