The First Handshake – May 1945

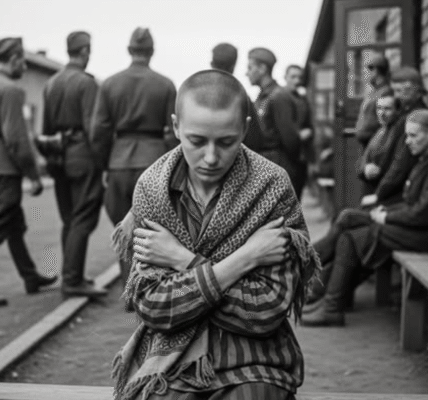

In May 1945, Europe was barely emerging from the abyss. The Second World War, the largest and most devastating war humanity had ever known, was drawing to a close. In the ruins of a torn continent, the survivors of the concentration camps, silhouettes shattered by hunger, fear, and daily humiliations, discovered for the first time the possibility of breathing without fear of immediate brutality. The liberation of the Nazi camps by Allied troops was a historic moment, but beyond the military event, it was embodied in tiny, intimate gestures that reflected the gradual return to humanity. Among them, a simple act, almost banal in other times: a handshake.

This gesture, immortalized in photographs from the time, remains one of the most powerful symbols of liberation. On one side, a Holocaust survivor, reduced to a shadow by deprivation and systematic dehumanization; on the other, a uniformed British soldier, bearing the promise of safety, restored dignity, and justice. Between these two men lies a chasm of irreconcilable experiences. And yet, at the moment their hands meet, something greater than words occurs: reconciliation with life.

For years in the concentration camps, physical contact had been synonymous with pain. The beatings, the humiliations, the brutal gestures dictated by a murderous ideology had left their mark on bodies and memories. Touch, that universal language of tenderness and closeness, had been perverted into an instrument of domination and terror. When the camp gates finally opened under the pressure of Allied armor, many survivors instinctively recoiled at the approach of the liberators. Fear had not disappeared overnight: it had become imprinted on the flesh and the mind.

This hesitation, often invisible to the eyes of soldiers drunk with victory, nevertheless reveals one of the most profound realities of liberation: it was not enough to open the barbed wire to erase years of persecution. The liberated prisoners remained prisoners of a bodily memory, a survival reflex forged by years of terror. Physical proximity, even benevolent, could seem threatening.

It was in this context that a survivor, amidst his still-disbelieving companions, dared to make the first gesture. His bony, trembling fingers rose to respond to the offered hand of a British soldier. The moment seemed suspended. The silence surrounding this encounter testified to the intensity of the moment: the other prisoners, frozen, watched with a mixture of stupor and hope. When finally the two hands clasped, a shudder ran through the assembly.

It wasn’t just a handshake. It was a declaration: I am still a man, I am no longer a number . It was also a mutual recognition: I see you, I welcome you, I respect you . For the survivor, this gesture marked a return to autonomy, the act of daring to touch and be touched without fear of the blow. For the soldier, it represented much more than a military formality: it embodied his humanitarian mission, his role as witness and protector.

The trauma of the Holocaust was not erased with a single gesture, of course. But that first handshake opened a breach in the shell of fear. It allowed survivors to begin to relearn what human contact meant—no longer as a tool of enslavement, but as a vehicle for recognition and equality.

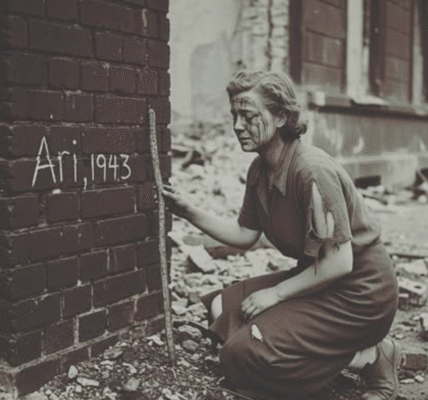

Psychologists who, decades later, would study the survivors’ memories would emphasize the importance of these micro-interactions. Far from grand speeches or ceremonies, it was often the details—a smile, a hand on the shoulder, a piece of bread shared—that marked the gradual return to life. Historical memory retains the important dates, but the intimate memory of survivors is built around these fragile moments when humanity reasserted itself step by step.

The British soldier, a young man trained in military discipline, found himself facing a reality that nothing had been able to teach him. Behind the liberated barbed wire, he discovered not only prisoners, but witnesses to a parallel world, that of industrial dehumanization. By shaking that hand, he was not only offering his physical strength: he was building a bridge between two worlds, that of freedom and that of oppression.

This gesture was also a political act, in the noblest sense of the term. It signified that Europe could not rebuild itself without recognizing the dignity of those who had been erased. Each handshake between a liberator and a survivor constituted an act of resistance against oblivion. It sealed a promise: never again .

Today, as we delve back into the archives of the Second World War, it is essential to recall the symbolic power of these gestures. The Nazi concentration camps were not only places of death, but also laboratories for the destruction of humanity. Holocaust survivors long carried the memory of this violence on their skin and in their hearts. But the liberation, in May 1945, also marked the reopening of the realm of possibilities: learning to get back on their feet, to rebuild, to relearn trust.

The photograph of this handshake has survived the decades as a visual testament. It does not depict liberation in the military sense, but in the profoundly human sense. In this encounter between a skeletal survivor and a soldier in impeccable uniform, we read the fragility of man, but also his resilience.

At a time when the contemporary world is still experiencing violence, exoduses, and refugee camps, this story remains relevant. It reminds us that human dignity is not restored only through treaties or military victories, but also through simple gestures. A handshake in a liberated camp in May 1945 continues to teach us that after extreme trauma, healing often begins with mutual recognition.

Whenever we revisit historical memory, it is crucial to bring these moments back to life. Behind the figures of the Holocaust, behind the millions of deaths, there were moments of grace, of rediscovered humanity. They remind us that even in the midst of the worst, humankind retains an infinite capacity to reach out, to rebuild a bond, to say we are still human .

The First Handshake of May 1945 is not just an anecdote, but a universal lesson. It illustrates how, after the Second World War , the return to life did not only involve the end of fighting, but also micro-gestures capable of restoring human dignity . This gesture between a concentration camp survivor and a British soldier remains one of the most powerful symbols of liberation .

In a world where violence and dehumanization continue to recur in other forms, this story invites us to reflect on the value of simple gestures. Sometimes, a handshake can speak louder than words: it expresses pain, memory, and also the hope of a reconciled humanity.