The Chimney Boy – The Story of a Little Chimney Sweep in the Victorian Era

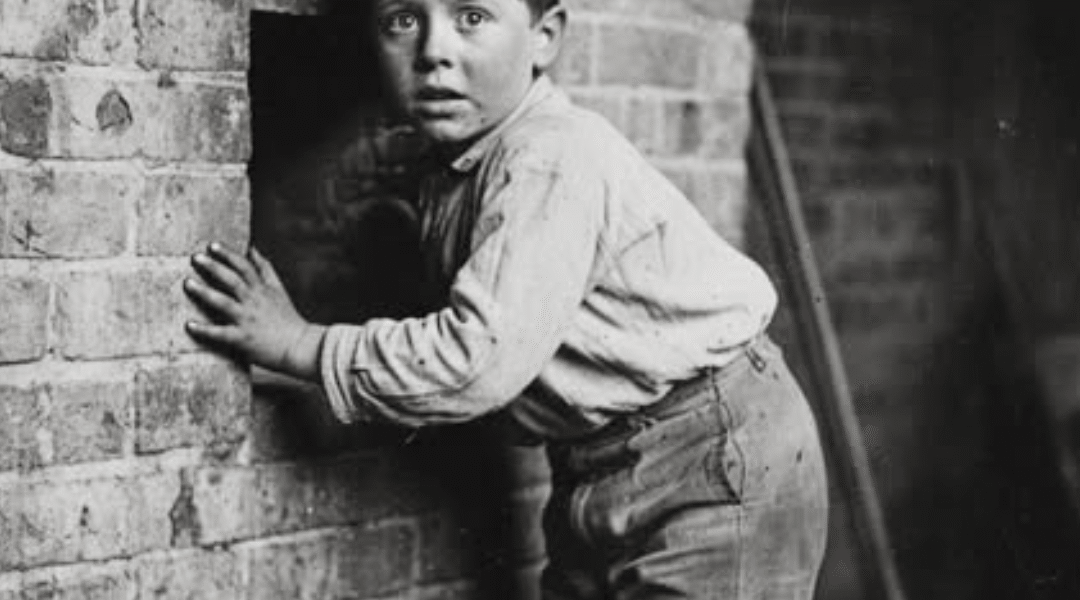

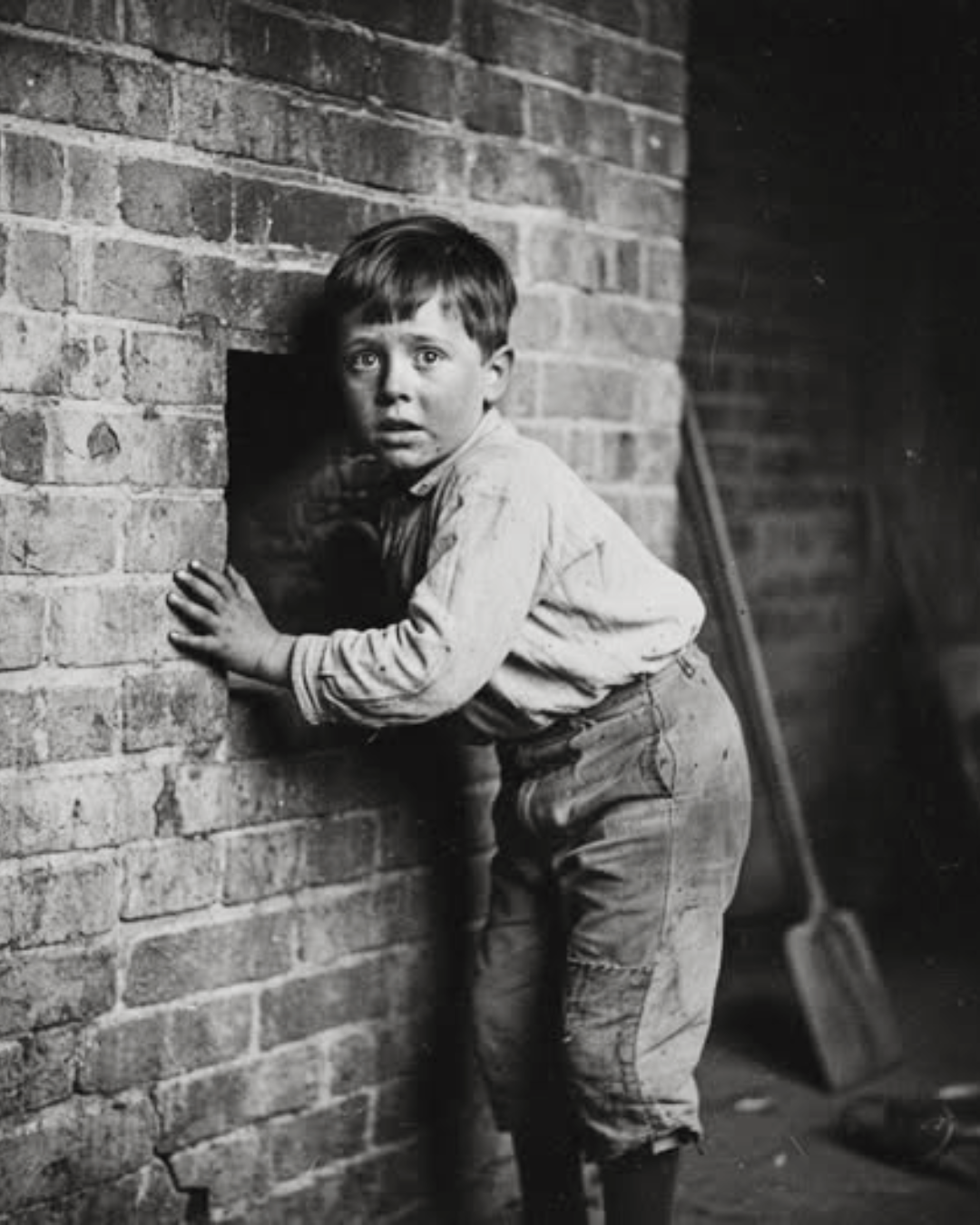

In the narrow shadows of 19th-century London’s backstreets, there existed a world that most bourgeois people preferred to ignore. It was a universe of soot and suffering, where childhood was not allowed to exist, because it was sacrificed on the altar of the Industrial Revolution . The image of a small boy, barely six years old, his eyes wide with fear at the gaping entrance of a chimney, alone sums up the brutality of an era when innocence was becoming a cheap commodity. This child’s name was Thomas G. Hayworth, but for many of his peers, names were lost in the smoke and squalor. They were simply called: the climbing boys .

The chimney sweep trade had long existed in Europe, but with massive urbanization and the rise of large factories, the demand for clean flues increased dramatically. The chimneys of Victorian homes, often narrow and twisting, could only be cleaned by very small bodies. Thus, hundreds of children were rented, sold, or abandoned to master chimney sweeps, who used them as living tools. At six years old, Thomas entered an eighteen-inch-wide flue for the first time, a space that looked more like a vertical coffin than a passageway.

The scene was always the same: at dawn, the teacher would wake the child, sometimes with blows from a stick, throw a coarse rag over his shoulders, and send him crawling into the darkness. Without gloves to protect his hands, without shoes to cushion his steps, the child climbed the sooty walls. Every movement left a bloody mark on his elbows and knees. The slightest misstep could trap him in the deadly narrowness of the shaft, and many children met a tragic end there, suffocated by the smoke or crushed by fear.

Thomas remembered the moment when, trembling and hesitant, he had placed his small hands on the rough bricks. The morning cold mingled with the still-warm heat of the unlit fireplaces. The acrid smell of soot invaded his lungs, triggering a cough that echoed through the chimney like a deadly echo. Behind him, the teacher’s voice cracked like a whip: “Faster, kid, or I’ll light the fire underneath!” It was not an empty threat. Many children had felt the suffocating heat of flames deliberately lit to keep them moving. With reddened eyes and burning throats, they climbed in panic, praying to finally see the light from a basement window.

The Industrial Revolution in England wasn’t just about steam engines and expanding factories. It also relied on these invisible children, exploited as a cheap and malleable workforce. Newspapers extolled the prosperity, the technical innovations, and the modern conveniences of coal and gas. But behind the red brick facades, an entire generation of children was losing their health and sometimes their lives. Child exploitation wasn’t a marginal accident: it was one of the pillars of Victorian economic growth.

As Thomas grew, his body bore the scars of his trade. His lungs, clogged with black dust, condemned him to a chronic cough. His joints remained marked by the scars of his forced climbs. This was called “chimney sweep’s disease,” an illness that struck children with relentless brutality, often causing scrotal cancer in adulthood, a direct consequence of constant exposure to soot. But by the age of ten, many did not even reach that age.

To survive, Thomas clung to small things: a loaf of bread distributed at the end of the day, a ray of light glimpsed at the top of a chimney, the stifled laughter of a friend when, for a moment, fear gave way to complicity. Between children, a fragile solidarity was formed. They knew that no one else would come to save them, because the laws, although debated in Parliament, were slow to translate into real protection.

In 1788, a first attempt at regulation had emerged in Great Britain, but it remained largely ignored. It was only in the mid-19th century, after decades of struggle, that campaigns led by philanthropists like Lord Shaftesbury led to stricter reforms. The Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act officially prohibited the employment of children under ten, and later under sixteen. But between the letter of the law and the reality of the backstreets, there was a gulf. Master chimney sweeps continued to recruit in secret, and families, crushed by poverty, still gave up their children for a few shillings.

Thomas was part of a generation trapped between the promises of progress and the brutality of poverty. His widowed mother had no choice. Hunger had forced her to deliver her son to the master, with the promise of a roof over her head and a few meals. But what the child found was an existence suspended between danger and exhaustion. Every morning, he slipped into the bowels of chimneys like a ghost, and every evening, he emerged a little more consumed.

Thomas’s story is not unique, but it is representative. It reminds us that the price of Victorian comfort—those glowing fireplaces in parlors, those warm hearths around which bourgeois families drank tea—was paid in the lives of sacrificed children. This contrast between the polished image of Victorian society and the harsh reality of the working conditions of the poorest illustrates the social divide of the time.

When we talk about health and safety at work today , when we talk about children’s rights, we must also think of these sooty faces. They are the silent witnesses of a time when childhood was reduced to a labor force. Old photographs, such as that of Thomas frozen in front of a brick opening, capture not only a moment of fear, but the very essence of a collective tragedy.

Because beyond horror, there is memory. Telling the story of Thomas G. Hayworth means refusing to forget. It is a reminder that every social advance has been wrested from the suffering of those who had no voice. And it is also a way of questioning our present: how many children, elsewhere in the world, continue to work in undignified conditions, hidden in the shadows of modern industries?

The Industrial Revolution transformed humanity, but it also revealed its darkest side. Between the sooty bricks and the burned lungs, one truth remains: no prosperity should ever be built on the destruction of innocence.

And perhaps, in Thomas’s frightened gaze frozen by the lens, we should see not only yesterday’s child, but a warning for the future.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.