The Child Being Carried — Bergen-Belsen, 1945

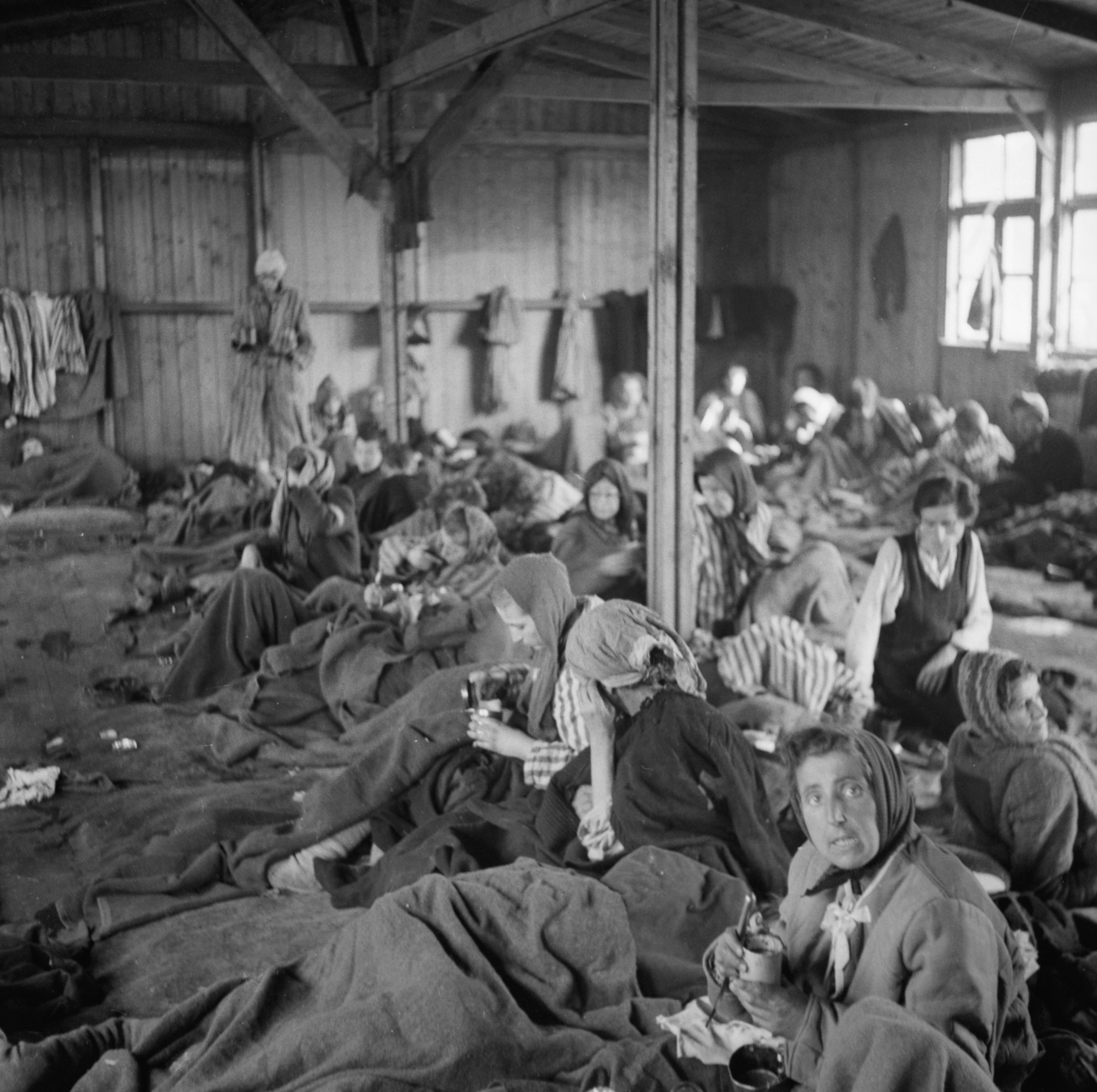

April 1945. When British troops crossed the barbed wire at Bergen-Belsen, they entered a world that defied human understanding. There, on the muddy, pain-saturated ground, lay a sea of gaunt figures, specters of men, women, and children reduced to shadows. Corpses littered the ground, piled high like dead wood, and the air was saturated with a smell so heavy it permeated every breath. For the liberators, the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp immediately became a symbol of absolute horror. But amidst the chaos, there were also moments of preserved dignity, silent solidarity, and shared compassion.

The story of the “Carried Child” belongs to this fragile but essential memory. It is said that in the days following the liberation, as the starving survivors lined up to receive a ration of bread distributed by the British soldiers, a young boy collapsed in the mud. His body, too fragile, could no longer support its own weight. Around him, the line advanced slowly, each step marked by the raw instinct of survival. The survivors no longer had the strength to speak, much less to stop. Yet, one man knelt.

This man was not his father. He was neither a relative, nor a brother, nor an uncle. He was a stranger, also broken by deprivation and hunger. But in this camp where everything had been done to destroy the very idea of human brotherhood, he decided to go against the grain. He took the child in his arms, hoisted him onto his back, and walked silently back to the table where the rations were being distributed.

The scene was witnessed by other survivors. The child, unable to speak, let his arms loosely cling to the man’s neck. This gesture, almost imperceptible, nevertheless contained a shattering intensity. In this trembling contact resided absolute trust: the child knew he could let himself be carried, that there was still a human hand strong enough not to abandon him.

In the archives of the Bergen-Belsen survivors, we find these kinds of anecdotes: small gestures, almost invisible in the face of the immensity of the tragedy, but which bear witness to the survival of humanity in the midst of hell. The man who carried the child sought neither recognition nor memory. He did not have the strength of a hero, only that of a human being who refused to look away.

The British liberators noted how the survivors, despite their extreme weakness, still tried to help one another. Some shared pieces of bread, others exchanged a blanket or a whispered word of comfort. In a context where hunger, disease, and death dominated, these gestures were not mere acts: they were life oaths.

The story of the Child in the Carry also illustrates a universal truth: survival was never purely individual. Holocaust survivors, whether they made it out alive from Bergen-Belsen, Auschwitz, Dachau, or Gross-Rosen, often testified that they owed their existence to someone who, one day, gave them a piece of bread, lent them a shoulder, or reminded them that they were still human.

In the days following the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, British military doctors faced a near-impossible task. The skeletal survivors sometimes weighed less than 35 kilos. Their bodies were no longer able to assimilate food. Many died after being given rations too quickly, victims of “refeeding syndrome.” In this context, the act of carrying a child became a symbol: saving a life did not always mean preserving it physically, but offering it a moment of human warmth, a breath of hope.

It is said that the child survived a few more days, literally carried by the strength of another. The man’s exhausted gaze was that of all the survivors: a fixity between pain and duty, an absence of tears where the eyes had no more water to cry. His back, hunched under the fragile weight of the child, was not an image of submission, but rather an affirmation: “We still have the capacity to carry one another.”

This story, passed down in fragments, has become one of those narratives that give life to memory. Historians insist on the need to keep alive not only the numbers—six million Jews murdered, thousands dead at Bergen-Belsen even after liberation—but also these moments of human survival. Every testimony, every anecdote, every murmur of compassion constitutes a response to the Nazi project of annihilation.

In the language of survivors, carrying a child meant more than a physical gesture. It was a metaphor for the postwar era: it was necessary to carry future generations, to pass on memory, to teach those who had not seen what the absence of humanity meant. Today, every story like that of the Child Carried becomes a building block in the edifice of collective memory.

Bergen-Belsen, liberated in April 1945, remains one of the most emblematic camps not only because of the scale of the tragedy—more than 50,000 people died there—but also because it was a place where photographic memory was intensely fixed. The images captured by British soldiers, showing the piled-up corpses and the survivors with emaciated faces, were broadcast around the world, leaving a lasting impression. But beyond these shocking images, there are also invisible stories, transmitted through the voices, diaries, and interviews of survivors. The Child Carried is one of them.

As a French writer, after thirty years of working on the memory of the Holocaust and on literature of testimony, I am struck by the silent power of this story. It tells us that in the darkest darkness, one human being remained capable of extending their back to another, of walking not just for themselves but for two. It tells us that the future, however fragile, can be born from this shared act.

Today, as direct witnesses gradually disappear, it is our responsibility to carry these stories forward. The Child Born of Bergen-Belsen is no longer here to bear witness. Nor is the man who raised him. But through us, their gesture lives on, reminding each generation that humanity never completely ends, even in the midst of horror.

Thus, in the mud of Bergen-Belsen, a fragile child and an exhausted man unknowingly wrote an essential page of history: one in which we learn that survival is not measured only in days lived, but in gestures transmitted, in burdens carried, in glances exchanged. And that in the silence of a liberated camp, the weight of a child on hungry shoulders was worth more than all military victories—for it was the victory of the human over the inhuman.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.