The Chain of Memory — When American Soldiers Liberated Gusen, 1945

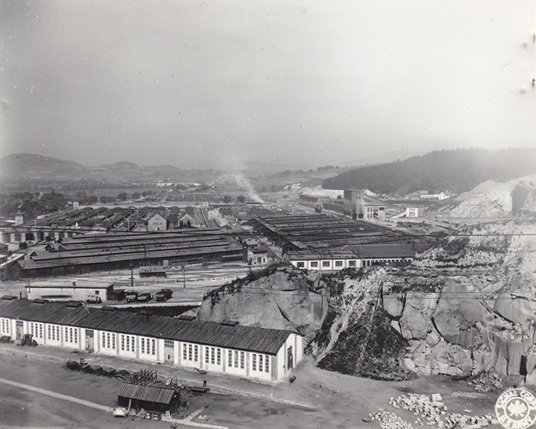

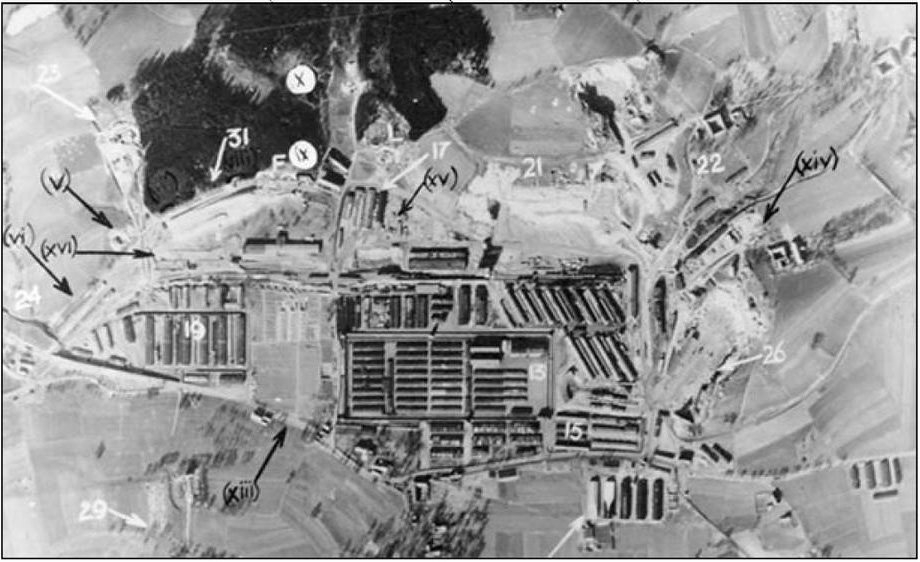

When the soldiers of the U.S. Army reached the Gusen subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp complex in early May 1945, they stepped into a nightmare buried beneath the mountains of Austria. What they found was not a battlefield, but a tomb of the living. Gusen was not simply a camp—it was a subterranean empire of forced labor, carved into the granite hills to feed the Nazi war machine.

For years, thousands of men had been sent there—Jews, political prisoners, Poles, Soviets, Spaniards, Italians—each stripped of their names and given numbers instead. Their task was to dig tunnels so immense that they swallowed the light, manufacturing aircraft parts and armaments deep underground. The air inside those tunnels was thick with dust and despair. Men labored twelve, fourteen, sixteen hours a day, their breath mixing with the cold vapor that clung to the rock. The only sounds were the grind of tools, the bark of guards, and the faint echo of chains dragging across stone.

Life inside the tunnels

Inside Gusen, life was measured in days, sometimes hours. Food was scarce—watery soup, a crust of bread, and punishment if one dared to pause. Beatings were constant. Prisoners collapsed under the strain, and when they did, their bodies were buried in the rubble or thrown into nearby pits. Some died with pickaxes still in their hands, their faces turned toward the faint trace of light that never reached them.

By 1945, over 70,000 prisoners had passed through the Gusen subcamps. Tens of thousands perished. The tunnels—code-named Bergkristall—were among the Third Reich’s most secret industrial sites. Here, in suffocating darkness, inmates built fuselages for the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter, the so-called “miracle weapon” that Hitler believed could turn the tide of war. But what those tunnels produced more than anything else was death.

Liberation at the end of the war

When the U.S. 11th Armored Division of General George S. Patton’s Third Army arrived at Mauthausen and its Gusen subcamps on May 5, 1945, the war in Europe was already days from its end. The soldiers had been hardened by battle—Bastogne, the Rhine, the push into Bavaria—but nothing prepared them for what they saw in Austria.

As the GIs climbed through the ruins, they expected resistance, perhaps snipers or remnants of the SS. Instead, they were met by silence broken only by the sound of wind passing through the mine entrances. Then, from the shadows, the prisoners emerged.

They came slowly, blinking, skeletal figures whose skin clung to bone. Some wore rags, others only striped uniforms that hung loose like empty sacks. Their eyes were wide, unfocused, struggling to adjust to the daylight after months—sometimes years—spent underground. They looked less like survivors than ghosts summoned from the depths.

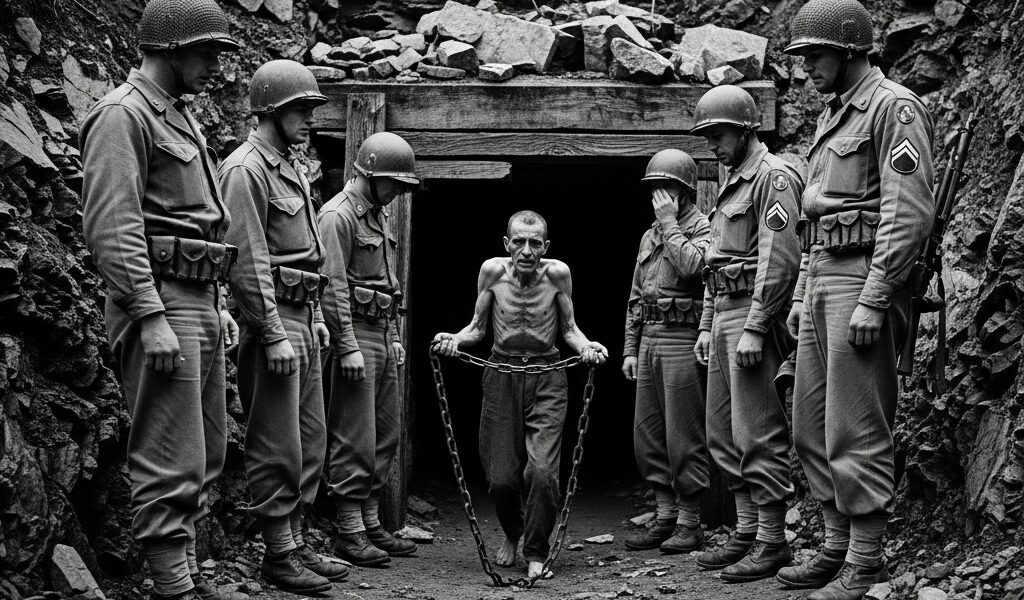

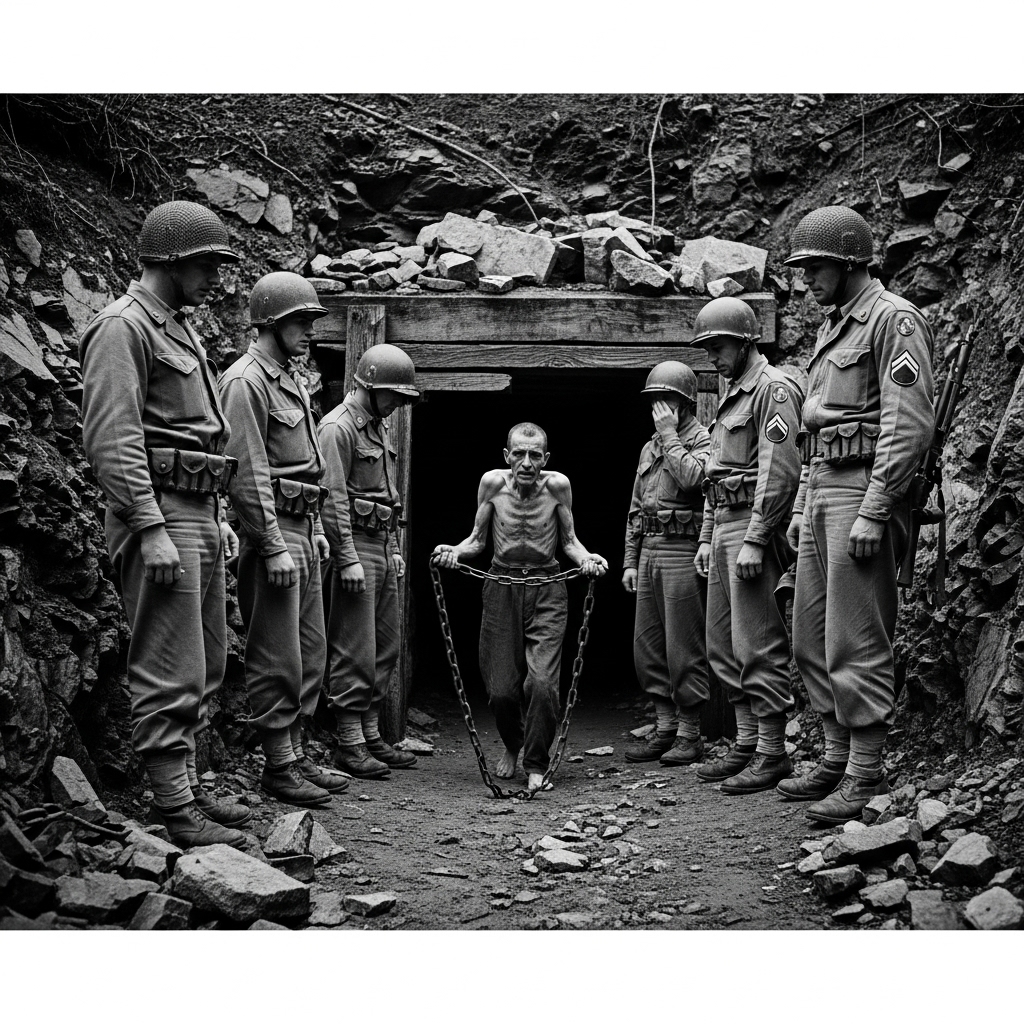

The man with the chain

Among them was one man who seemed barely alive, his ribs exposed, his steps uncertain. He emerged from the mouth of a tunnel, dragging something behind him. At first, the American soldiers thought he was still bound. Then they saw: the chain was not attached to him at all.

He carried it in his hands.

The man stopped before the soldiers, his gaze hollow but resolute. One of the Americans—a sergeant, young and shaken—took a hesitant step forward. “Why do you carry that chain?” he asked softly.

The prisoner looked up, his voice little more than a whisper. “So I will never forget,” he said. “What they did to us.”

The words hung in the air like a prayer. The chain clinked faintly as he lifted it—a sound small enough to be lost in the wind, yet powerful enough to echo across history.

For that soldier, and for the men standing around him, the meaning of the war condensed into that one moment. It was not about territory, nor politics, nor the defeat of an empire—it was about the restoration of humanity, one soul at a time.

The soldiers’ silence

The Americans had seen combat. They had seen death. But this was different. Some turned away; others removed their helmets in respect. They offered water, blankets, rations, but the prisoners wanted more than food—they wanted recognition, proof that they were no longer invisible.

A medic recorded later: “We gave them chocolate, and they cried. We offered them bread, and they trembled. One man kissed my boots. I didn’t know what to do.”

The men of the 11th Armored and 41st Cavalry were trained to fight; they were not trained to confront the collapse of civilization. Yet they did what they could. They opened the camps, tended to the wounded, and documented everything. Their photographs, preserved in archives today, bear silent testimony: rows of bodies, skeletal survivors, tunnels filled with machinery, and that haunting image of a man with a chain.

The meaning of the chain

For historians, the Gusen chain became a symbol—a tangible reminder of the industrialized cruelty of the Nazi regime. But for the man who held it, it was something deeper. It was memory forged into metal. Each link represented a day of suffering, a friend lost, a name erased. To drop it would be to forget.

In the years after liberation, survivors of Gusen and Mauthausen told their stories to anyone who would listen. Some emigrated to America, some stayed in Europe to rebuild their lives from ashes. Many spoke of the tunnels, the hunger, the sound of pickaxes in the dark. But almost all remembered the moment the Americans arrived—the moment daylight returned.

Rebuilding and remembering

The Gusen complex was later dismantled. The tunnels were sealed, the machinery removed, and the site partly reclaimed by the forest. For decades, the area was left to decay. Only in recent years has there been renewed effort to preserve what remains—to build memorials, mark entrances, and ensure that future generations can see where darkness once ruled.

Visitors to the Gusen Memorial today can still sense the weight of the past. The tunnels, though closed to the public, remain beneath the ground—cold, silent witnesses to a time when human life was valued less than a machine part. At the entrance, a plaque bears the words “Never Again” in multiple languages. It is both a warning and a promise.

The soldier’s reflection

One of the American soldiers who helped liberate Gusen, decades later, wrote in his diary:

“I have carried that man’s face with me all my life. Not the chain—his face.

I saw in him the strength to survive what none of us could imagine.

I went to war thinking I would fight for victory.

That day, I understood I was fighting for humanity.”

He never learned the prisoner’s name. Perhaps no one ever did. But in that encounter, amid the ruins of war, they shared something eternal—a truth about endurance, about the will to remember, and about how freedom, once restored, carries the duty to bear witness.

Legacy and SEO context: remembering Gusen and the Holocaust

Today, when people search for the history of Gusen Concentration Camp, Mauthausen Liberation, or American soldiers liberating Nazi camps, they uncover this story not only through photographs and records but through testimonies that refuse to fade. Each article, documentary, and memorial ensures that the tragedy of Gusen remains visible. In a world still scarred by war and hatred, stories like this one hold power—reminding us that remembrance itself is resistance.

The keywords that echo through history—Holocaust survivors, American troops, WWII liberation, Nazi concentration camps, Mauthausen Gusen tunnels, human resilience, freedom and remembrance—are not just data points for algorithms. They are markers of conscience.

The chain’s final echo

If you visit the Gusen Memorial in modern-day Austria, you will find replicas of the rusted chains once used on prisoners. They hang silently behind glass. But in one corner, near a tunnel entrance, lies a single chain link—unearthed decades later during excavation. Its surface is corroded, yet you can still see where a hand once held it tight.

That hand may have belonged to the man the Americans saw in 1945. Or perhaps to another who shared his fate. It doesn’t matter. The chain, like the story, belongs to them all.

When the soldiers left Gusen, they carried more than their weapons and uniforms. They carried memory. And long after the tunnels filled with silence again, the sound of that clinking chain—the sound of survival—still rings across time.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.