The Book of Names — Theresienstadt, 1944

In Europe devastated by the Second World War, in the midst of Nazi horror, there were small gestures of resistance that official history has long forgotten. These gestures were not made of weapons or spectacular uprisings, but of silence, paper, and improvised ink. It was in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1944 that a group of women prisoners, driven by incredible courage, undertook a mission that went beyond their personal survival: to preserve the memory of those whom the Nazi regime wanted to erase forever. Their work was much later named “The Book of Names ,” a fragile but immortal testimony that still defies oblivion today.

Theresienstadt, or Terezín in Czech, was presented by Nazi propaganda as a “model camp.” In reality, it was a transit point to Auschwitz, Sobibor, or Treblinka, an antechamber of death where hunger, disease, and fear reigned supreme. The inmates—intellectuals, artists, the elderly, and Jewish children—lived crammed into unsanitary barracks. Behind the walls of this fortified city-turned-prison, illusions quickly faded. Every day, convoys departed, and each departure almost always meant a definitive disappearance.

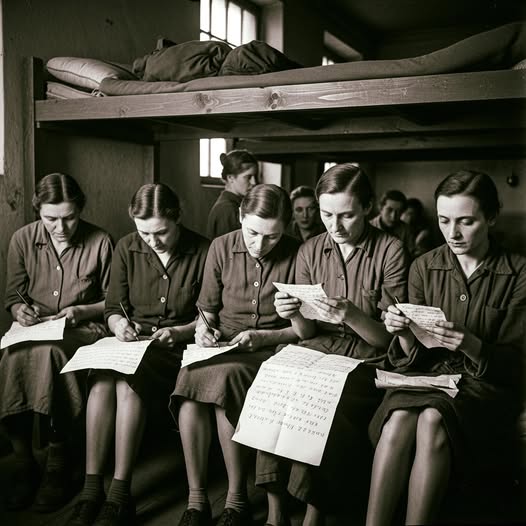

Among these women locked in a cramped dormitory, a secret pact was born: if the Nazis wanted to erase the names, they would save them. The name, this simple combination of letters, became a weapon against oblivion. Every evening, by the flickering light of a candle or a stolen lamp fragment, they wrote on small pieces of paper the identities of those who had disappeared. The means were paltry: coal rubbed against stone to make ink, torn scraps of cloth or discarded envelopes to replace notebooks. But the conviction was immense.

Writing in a concentration camp was an act of rebellion. Every line traced exposed these women to torture, to summary execution. Yet, each night, the notebook grew. The names were added one by one, like a funeral litany: children, old people, mothers, fathers, artists, doctors, teachers. Each of these names was a universe torn from barbarism. Each represented a story, a memory, a trace that the Nazis would not have the last word on.

At night, in the dim light, the women read these names in hushed voices. It wasn’t just writing: it was a liturgy, a ritual of spiritual survival. “We wrote so they wouldn’t die a second time,” one survivor confided after the war. In the concentration camp world where death was reduced to numbers, these women restored the victims’ dignity: that of being remembered by name.

As the months passed, the list became a veritable Book of Names . It contained more than 800 identities. Some pages bore the traces of tears falling onto the still-damp ink, others were crumpled by the trembling hands that held them. These pages were not just a document: they were a paper tomb, a clandestine cemetery for those who would never have a stone or flowers.

As the Nazis began to lose the war, rumors of liberation reached the walls of Theresienstadt. The women knew that the book’s survival was even more important than their own. They decided to hide the manuscript under the floorboards, deep in a hiding place concealed by rags. They didn’t know if they would ever see the light again, but they wanted this testimony to survive, no matter what.

In May 1945, when Allied troops reached the camp, the Book of Names was discovered . The shocked soldiers opened it and immediately understood the document’s significance. Each page revealed a silent struggle: not one of arms, but of memory. This was not a cold, distant administrative list. It was a dirge, a handwritten prayer, the final gesture of prisoners who had refused to surrender to total annihilation.

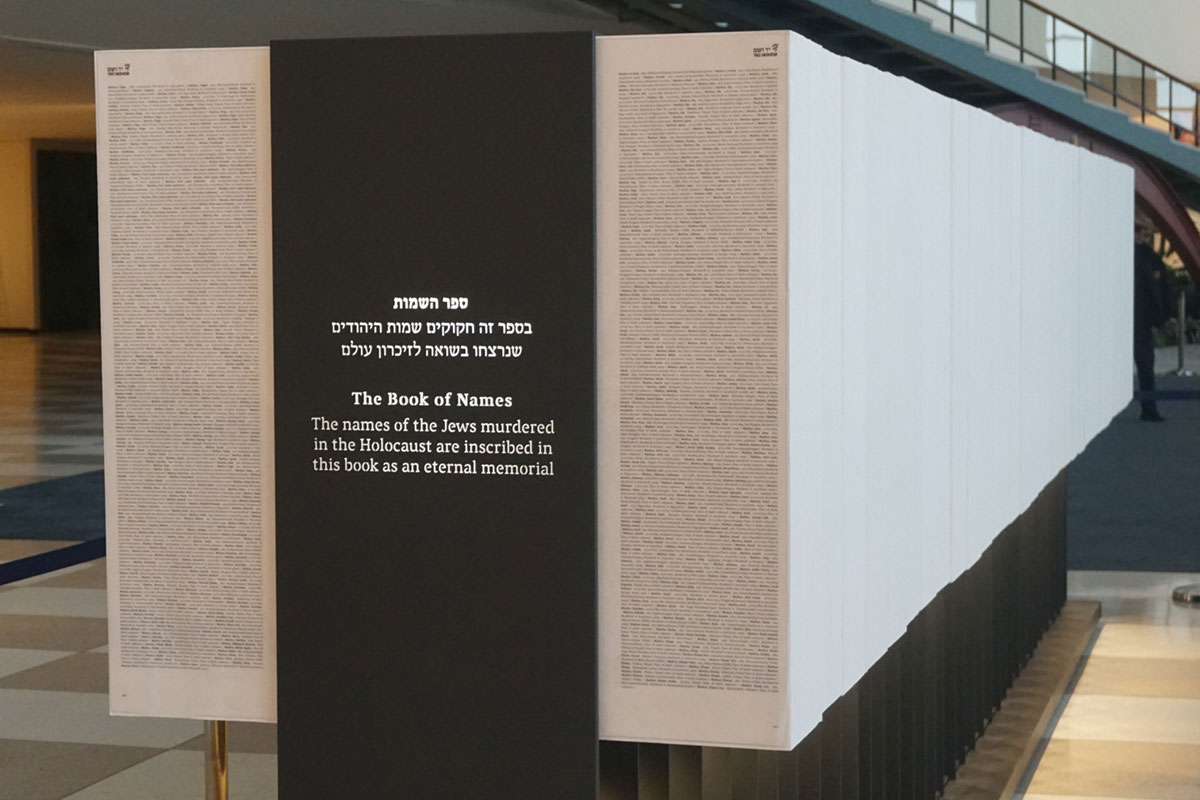

Today, this book rests in a museum, protected behind glass, but alive in the collective memory. Survivors of Theresienstadt often described it as “our cemetery, because for so many of our dead, there is no grave.” The Book of Names has become a universal symbol: it reminds us that in the most utter barbarity, the act of remembrance is a form of resistance, and that the Holocaust cannot be reduced to impersonal numbers.

Each time a visitor reads these names, they participate in this act of resistance that began more than seventy years ago. By pronouncing these identities, we give new life to those who were reduced to nothing. This is the power of memory: to transcend death, to combat oblivion, to restore each person’s uniqueness.

The story of the Book of Names also holds a universal lesson for our contemporary world. In an age where misinformation threatens historical truth, where some dare to deny the Holocaust, this document stands as irrefutable proof. This is why historians, teachers, writers, and survivors insist on passing on these stories. Fighting against forgetting also means protecting our future.

This story resonates today in museums, classrooms, libraries, and even on the internet. Every time the Book of Names is discussed, historical truth is pitted against the forces of denial and indifference. This is why it is so important to integrate this testimony into education and collective culture.

In the horror of the Theresienstadt camp, as hunger, disease, and fear decimated the prisoners, a few women armed only with courage, paper, and improvised ink managed to save more than their own lives: they saved memory. Their silent gesture, written in secrecy, is today one of the most powerful cries of resistance preserved in history.

Because to remember is to resist. And as long as we read and pass on these names, they will never disappear.