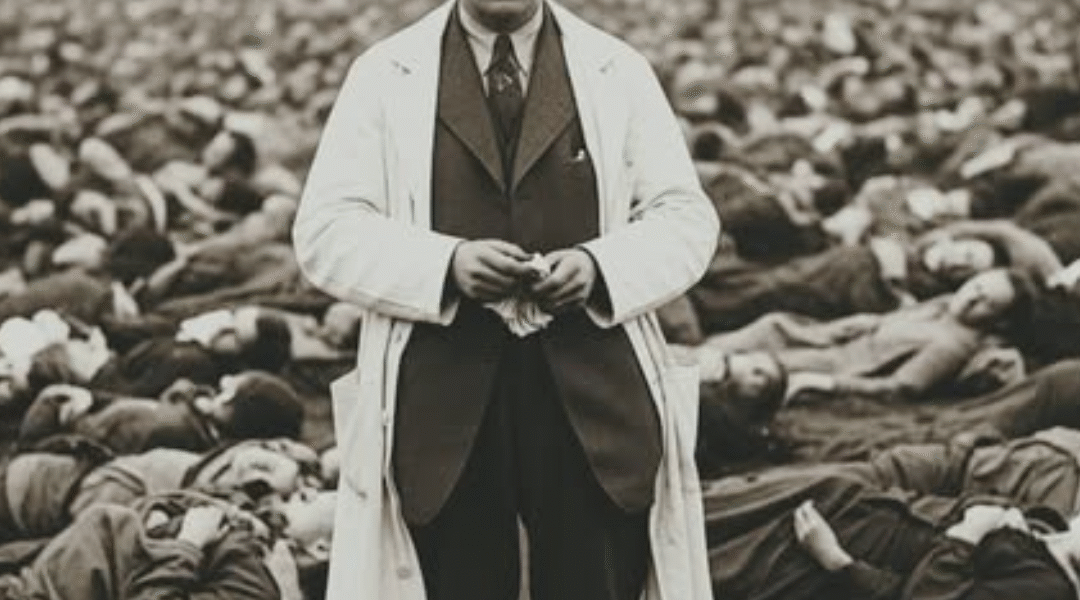

“The Belsen Doctor” — Bergen-Belsen, 1945

In April 1945, when British troops crossed the barbed wire of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp , they discovered an apocalyptic landscape. On a land soaked with mud and blood, more than 60,000 starving survivors wandered among thousands of rotting corpses. Bodies littered the ground, piled in pits or abandoned along the barracks. The unbearable stench of death hung in the air, and the muffled screams of the sick rose in the chilling silence that no words could convey.

In the midst of this hell, one man would go down in history with his courage and humanity: British military doctor Glyn Hughes , quickly nicknamed “the Doctor of Belsen” by survivors. This officer, trained in the rigor of military hospitals and hardened by the horrors of war, suddenly found himself facing an inhuman challenge: saving tens of thousands of lives with almost nothing, in a camp where death seemed to have triumphed over all forms of hope.

When Hughes entered the camp on April 15, 1945, his eyes met a vision no war could have prepared for. The Nazis, before fleeing, had left behind indescribable chaos: typhus, dysentery, tuberculosis, famine —every barracks a hotbed of epidemics. The inmates were nothing more than shadows, living skeletons, unable to walk, sometimes even to lift their heads. Many, lying on the ground, simply awaited death.

The British army had entered to liberate a camp. But Hughes understood that the open-air cemetery now had to be transformed into a makeshift hospital . Its role went beyond military: it became the last line of defense between total annihilation and survival.

In the early days, the doctor had only a handful of medicines, a few medical teams, and unwavering courage. Nearby hospitals were already overwhelmed by the influx of war wounded, and medical resources were scarce. Yet Hughes made a decision that changed the fate of thousands of prisoners: he transformed part of the camp into a medical center, improvising treatment rooms in the barracks that were still standing.

Every day he walked among the corpses, giving orders, comforting the dying, attempting the impossible. It was necessary to fight typhus , the disease transmitted by lice, which was decimating the survivors. Antibiotics were still non-existent on a large scale, and the only treatment consisted of isolating the sick, washing the bodies, and burning the infested clothing.

But how could anyone isolate in a camp where everyone was already infected? Hughes then came up with a radical solution: he brought in decontamination units, ordered the mass disinfection of the barracks, and the incineration of the corpses. Day and night, he supervised this relentless fight against the epidemic, aware that every hour lost meant hundreds more deaths.

Beyond care, Hughes understood that the survivors needed more than medical treatment: they needed to be restored to their humanity . Hunger was unbearable, but giving too much food to weakened bodies risked killing them. So the doctor introduced adapted diets, based on light soups, before gradually reintroducing a more solid diet.

Survivors later remembered this doctor with a grave look, dressed in a white coat stained with dust and sweat, who would come and sit beside them. He never took his eyes off their wounds, their thinness, their suffering. Unlike others, he did not look at them as ghosts, but as human beings.

One survivor recounted years later:

“He gave us medicine, but more than that, he gave us back our dignity. For the first time in years, we were treated like men and not like animals.”

Despite his efforts, Hughes had to face the inevitable: thousands more prisoners died after liberation . Typhus, dysentery, and hunger had taken their toll for too long. Between April and June 1945, nearly 13,000 more people died in the camp.

But thanks to the doctor’s organization and the gradual arrival of reinforcements—notably the Red Cross and volunteer doctors— ten of thousands of survivors were saved . It was a silent victory, wrested from the very heart of the horror.

Glyn Hughes never truly left Bergen-Belsen. Even after the camp closed, his name remained associated with this struggle against death. He was called to testify at the Nuremberg trials, describing in detail the atrocious conditions he had witnessed. His calm, measured voice carried the weight of thousands of lives.

He explained to the judges that the prisoners had reached a point where medicine alone was no longer sufficient. It took a colossal human effort, a mobilization of soldiers, doctors, and volunteers, to prevent total extinction. His words helped establish the historical truth about Bergen-Belsen, against those who were already trying to minimize or deny the extent of the crimes.

Today, when we hear the name Bergen-Belsen , we think of the unimaginable suffering, but also of those figures who, in the pitch black, rekindled a flame of hope. Doctor Hughes embodies this resistance of humanity in the face of inhumanity.

His legacy extends beyond medicine. He reminds us that, even in the midst of chaos, one man can make a difference by refusing to look away. In a place where everything called for indifference, he chose action. In a space where the Nazis had destroyed human dignity, he knew how to restore it.

For the survivors, he was not just a doctor: he was living proof that compassion could overcome barbarism. Many of them, who later settled in Israel, the United States, France, or elsewhere, told their children and grandchildren the story of the man in a white coat who had walked among the corpses to reach out to them.

The Bergen-Belsen site is now a place of remembrance. Where death and desolation once reigned, a memorial now stands, reminding future generations of the importance of never forgetting. The mass graves are still visible, marked with simple headstones, as the names of so many victims remain unknown.

In this silence, the echo of the Doctor of Belsen’s footsteps still seems to resonate. Every visitor who walks these lands hears this question in his mind: what would we have done in his place? Would we have had the strength to fight against the impossible?

Hughes’s memory is an answer: yes, it is possible to resist despair. Yes, it is possible to save lives when all seems lost.

The story of Doctor of Belsen , the British physician Glyn Hughes, is that of a man who transformed a field of death into a battlefield for life. In the face of famine, epidemics, and inhumanity, he demonstrated exemplary courage and determination.

He didn’t save everyone. But he saved enough to give meaning to the word “humanity.”

In a world where the atrocities of war had reduced human beings to dust, his gesture became a light. A fragile light, but enough to show that dignity and compassion can survive barbarism.

And perhaps it is here, at the very heart of Bergen-Belsen, that Glyn Hughes’ greatest victory lies: having proven that, even in the abyss, man remains capable of humanity .

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.