The Auschwitz Scarf — The Fabric of Memory

At the icy dawn of January 27, 1945, the gates of Auschwitz finally opened. The winter wind blew through the barracks, carrying with it a strange silence—that of the end, or perhaps that of a beginning. The survivors, dazzled by the light of freedom, advanced slowly, still prisoners of their gestures, their fears, their memories.

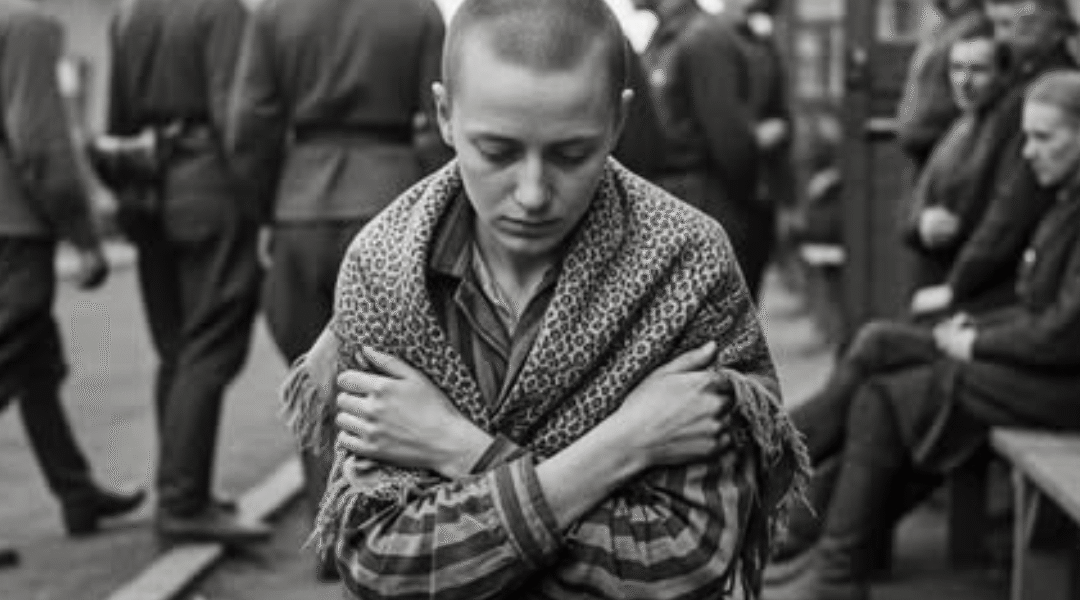

Among them, a young woman with a shaved head, her gaze lowered, clutched a torn old scarf. This piece of fabric, worn, soaked by tears and snow, was all that remained of her former life. And perhaps it was this, more than freedom itself, that kept her standing.

Her name was Léa , or at least that was the name she remembered having. The years spent in the camp had erased even the music of her first name. Yet every time her fingers touched the scarf, her mother’s voice returned. She remembered the day she received it, one April morning, before deportation: a simple square of wool, embroidered with pale threads, tied around her neck. Her mother had whispered to her,

“Here, my darling. It will keep you warm.”

No one knew that this scarf would become a symbol of survival, a thread of love amidst the cold and death.

During the endless days of forced labor, Léa hid the scarf under her striped jacket, against her chest. She had nothing left, no ring, no photo, no name sewn onto a piece of clothing. But that piece of fabric still carried a scent—that of home, of warm bread, of her mother’s arms. In a place where everything was designed to erase humanity, the scarf became her silent rebellion.

When the other prisoners closed their eyes to forget, Léa closed hers to remember.

The guards shouted, the dogs barked, the snow fell on the tin roofs. Each day resembled the previous one, a relentless process where bodies were counted more often than the living. Yet, in the night, under the damp straw of the shack, she touched the scarf and murmured silent prayers. It was her way of saying: I’m still here .

And through this imperceptible gesture, she continued to exist.

When liberation came, Léa was speechless. How can one express freedom to those who have known only fear? How can one speak of rebirth when one leaves a place where death had a familiar face?

The stunned Soviet soldiers looked at these ragged figures staring back at them without smiling. Léa sat on a bench in front of the barracks, her scarf tightly wrapped around her thin arms. She was trembling, not from the cold, but from the dizziness of still being alive. The other survivors spoke in low voices, hesitating between joy and guilt. Many wondered: Why me? Why did I survive when so many others stayed?

But Léa remained silent. In the silence, she stroked the scarf. She knew that this piece of wool had been her voice when she no longer had the strength to speak.

The days that followed were a blur, like a broken dream. They were taken to a makeshift hospital, where doctors tried to breathe some life into these emaciated bodies. Léa always kept the scarf close to her, refusing to let it be washed or thrown away. A soldier, intrigued, asked her one day,

“Why keep it, miss? It’s in tatters.”

She replied gently,

“Because it survived, too.”

The soldier fell silent. He understood that this fabric carried a story that no words could replace. In a world where names, faces, and prayers were burned, this scarf had become proof of existence. An indestructible trace.

Over time, the survivors of Auschwitz were scattered throughout Europe. Some returned home, others were homeless. Léa walked for weeks to find a village that no longer existed. Where her home once stood, there was only a field and ashes. She sat down by the side of the road, took the scarf from her pocket, and placed it on her knees.

It was no longer a garment. It was a grave, a bond, a promise.

She closed her eyes and saw her mother again, her hands, her smile. The memory was so real that she was almost afraid to reach out. In that suspended moment, she understood that memory doesn’t need walls to exist. It lives in objects, in gestures, in looks. And sometimes, in a simple piece of fabric.

Years passed. Léa remained in France, in a small town in the East. She almost never spoke about the camp, except once, to a journalist who had come to write about the liberation of Auschwitz . He wanted figures, facts, dates. She showed him the scarf, carefully folded in a wooden box.

“This is my truth,” she said. “This scarf is the story of a mother who wanted to protect her daughter, and of a daughter who refused to forget.”

The journalist remained silent. In that small square of worn wool, he suddenly saw everything that books don’t say: fear, tenderness, survival, humanity. He understood that memory is not limited to stone monuments, but to those tiny objects that carry the weight of the world within them.

Today, Léa’s scarf rests in a museum of memory, behind a discreet glass window. Visitors stop there and read the plaque: Scarf of an Auschwitz survivor, 1945. Few know that this simple object survived the Second World War, hidden under a striped jacket, pressed against a heart beating between life and death.

But those who linger see more than a fabric: they feel the warmth of a love that defied barbarity.

And that’s the power of this true story: in a world where hatred wanted to erase everything, one woman kept a symbol of love alive.

A scarf—fragile, frayed, but invincible.

Historians often say that the liberation of Auschwitz marked the end of a nightmare. But for the survivors, it was above all the beginning of a long fight against oblivion. Each carried with them a trace, a fragment of life to preserve. Some had letters, others a photograph, a ring, a button… Léa had her scarf.

And this scarf alone contained everything: fear, faith, resistance, humanity.

This is why he continues to speak today. To each visitor, he whispers:

Remember.

Remember that once, in a world of darkness, a simple piece of wool stood up to oblivion.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.