April 15, 2015 — Seventy years later

The wind blew gently across the fields of Lüneburg, sweeping the grass, a green almost too tender for a place so heavy with mourning. The sky was low, the light timid, and the silence seemed deeper than usual. It was a silence that belonged only to those places where memory weighs more heavily than time.

The young woman’s name was Claire. She was thirty-two years old, with a face both serious and serene, the face of someone who carries the memory of another. In her hand, she held a small piece of gray fabric, frayed at the edges—a fragment of a rough, worn military blanket. Her grandmother, Ruth, had kept it all her life. This piece of wool, torn from the blanket that had enveloped her when she was liberated from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, had become a family talisman, an invisible thread linking three generations.

On April 15, 2015, seventy years to the day after the camp’s liberation, Claire walked slowly down the memorial’s path. The wind made her dark hair dance and carried with it the scents of damp earth and fresh flowers. In her pocket, she felt the softness of a small white satin ribbon, the one she had chosen to tie around the blanket. She had been preparing this gesture for months.

As a child, she remembered the stories her grandmother whispered in hushed tones. Ruth rarely spoke. When she did, her words were simple, spare, yet imbued with a gravity known only to those who witnessed such events. “The cold was our first fear,” she would say. “The cold and hunger, for one makes you shiver, the other gnaws at you.”

Claire had grown up with these phrases hanging in the air like unfinished prayers.

She didn’t understand everything, but she felt it.

And to feel it was already to remember.

Kneeling before the memorial stone, Claire placed the strip of fabric at the foot of the monument. She smoothed it with her fingertips, as if to soothe a wound. Then she placed three white roses beside it—one for Ruth, one for the departed, and one for those who still live, bearers of the memory.

Her lips barely murmured,

“For you.”

Just two words, but they contained everything.

A tribute, a thank you, a promise.

The wind seemed to respond, lifting the grey wool, making it tremble for a moment before it fell gently back down.

It was like a sign—as if the past itself had recognized this gesture.

Around her, the field was almost empty. A few visitors were laying flowers, others stood motionless, eyes closed. Memory had its own rituals. Claire then felt the profound meaning of what she was doing. This small fragment of blanket was not just a physical memento. It was a bridge. A tangible link between yesterday’s pain and today’s fragile peace.

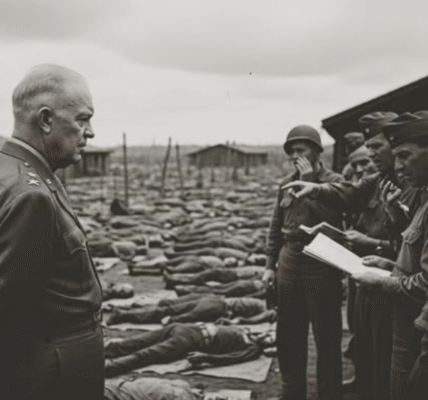

For years, Claire had studied the archives, the war diaries, the testimonies. She knew what Bergen-Belsen had been: a camp without gas chambers, but where death hung in the air, in the mud, the fever, the hunger.

Ruth had been among the survivors of that place of darkness and fever.

During the liberation, a British soldier had given her a blanket. It was that piece that Claire now held.

As she gazed at the stone engraved with her grandmother’s name, Claire reflected on the incredible power of transmission. How could such a simple object hold so many stories?

Objects don’t speak, but they listen.

And when you touch them, they respond.

Ruth had repeated this idea to him one day, in a whisper, just before she died:

“What remains is not the words, but what we transmit without speaking.”

On April 15, 2015, everything fell into place.

Claire understood that her gesture was not a farewell, but a continuation.

The memory no longer belonged solely to the past; it now lived on through her, in this vibrant and fragile present.

She thought of all those scattered families, of those grandchildren of survivors who, like her, silently carried the legacy of trauma. The collective memory of the Holocaust was not only a historical duty, it was a deeply personal responsibility.

And yet, how much longer would this memory last?

Seventy years.

Soon a hundred years.

The witnesses are passing away, but their traces remain — in objects, in gestures, in words whispered between generations.

This is how memory survives: not through speeches, but through tenderness.

The wind suddenly picked up, stronger than before.

The trees, lined up like an honor guard, began to bend slightly, their branches trembling in unison.

Claire had the strange feeling that the wind was carrying voices from the past.

She closed her eyes.

And for a moment, she thought she heard a whisper, almost a breath:

“Thank you.”

A shiver ran through her. She wondered if she had dreamt it.

But deep down, she knew.

The field at Bergen-Belsen today bears no resemblance to the camp of yesteryear. Grass has reclaimed the mass graves, nature has taken its course. The birds sing once more.

But beneath every blade of grass, beneath every stone, lies a story.

It is a place where the earth itself remembers.

Claire took a picture of the stone, the fabric, and the flowers. Not for social media, no. For herself. For her children, someday. She wanted to show them, not the pain, but the dignity.

The dignity of those who survived, and that of those who remember.

That same evening, in her hotel room, she reread the letters Ruth had written in the 1950s, when she was trying to rebuild her life.

One of them read:

“The hardest thing is not to survive, but to continue to love the world after seeing it destroy itself.”

Claire placed the letter next to the photo. She felt a new peace settle within her.

She understood then that memory was not a burden, but an act of love.

The silent power of objects

Historians often speak of “material memory.”

This concept, found in Holocaust museums, illustrates how objects—a pair of shoes, a piece of blanket, a suitcase—become living archives of humanity.

But for Claire, this notion went beyond the academic realm.

This fragment of blanket was a heartfelt heirloom, a symbol of resilience passed down through time.

He reminded us that survival does not end with the end of the war: it continues, generation after generation, in the ability to transmit, to understand, to feel.

This is where the true duty of remembrance lies:

Not in the simple repetition of facts, but in the recognition of the link between the living and the dead, between yesterday and tomorrow.

Leaving the memorial the next day, Claire turned around one last time.

The white roses still lay there, upright despite the wind.

The grey fabric, however, seemed to have melted into the ground, as if absorbed by the earth that remembered.

She smiled.

Ruth would have loved that moment.

No tears, no grand speeches. Just a gesture. Simple, sincere.

She whispered,

“As long as I breathe, you will not be forgotten.”

A living memory

Seventy years after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, the number of survivors is dwindling.

But their descendants still carry the flame.

This flame is not only that of remembrance, but also that of responsibility: to tell the story, to teach, to understand.

The story of Claire and Ruth reminds us that the memory of the Holocaust is not confined to museums.

It lives on in every act of love, in every act of transmission, in every glance cast upon a faded photograph.

Memory is a living legacy.

And as long as it circulates, so does hope.

Epilogue: The Breath of the Wind

Before leaving, Claire had picked up a small pebble and placed it on the memorial stone — according to Jewish tradition.

An ancient, symbolic gesture, a sign that the memory endures.

When the evening wind blew one last time across the field, it made the roses tremble and lifted a few blades of grass.

And in this imperceptible movement, something invisible was transmitted — a breath, a memory, a presence.

Seventy years later, Ruth’s memory still lived on.

Not in books, nor in museums, but in the heart of a young woman who knew that the past is never truly buried.

It transforms, gently, into love.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creative reasons and suitability for historical illustration purposes.