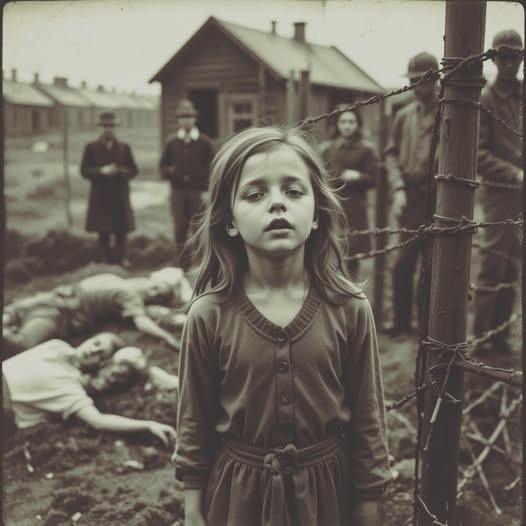

The Girl Who Sang to the Dead — Treblinka, 1943

In the heart of the Holocaust, where silence was meant to reign and humanity was reduced to ash, there lived—if only briefly—the memory of a child who refused to let the world forget. Her name was never written down. Her face, fragile as it was, vanished with millions of others swallowed by Treblinka, one of the deadliest Nazi extermination camps. Yet the prisoners whispered her story, and somehow, across decades, it survived: a girl of no more than twelve years old, standing by the barbed wire, singing softly to the dead.

“They must not leave in silence,” she is remembered to have said.

This is not just a Holocaust story. It is not only the history of Treblinka, or the echo of a child’s song. It is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, to the defiance of innocence, and to the sacred duty of memory. In the darkest corners of human history, a child’s lullaby became a form of resistance.

To understand her voice, one must understand Treblinka itself. Unlike Auschwitz, Treblinka was not built as a labor camp. It was a factory of death. Constructed as part of Operation Reinhard, its single purpose was the extermination of European Jewry. Between July 1942 and October 1943, nearly 900,000 Jews were murdered there—most within hours of arrival.

The camp was designed with chilling efficiency. Trains arrived daily, packed with men, women, and children, deported from ghettos across Poland and beyond. Upon stepping off the cattle cars, the deception began: signs falsely promising showers and resettlement, guards barking orders to move faster. But in truth, almost all were marched directly into the gas chambers. Only a fraction—often young, strong, or deemed “useful”—were kept alive to serve as prisoners, forced into labor that maintained the machinery of death.

For those who lived beyond the first hours, survival was a cruel paradox. Every breath was borrowed, every day a postponement of execution. Hunger gnawed, disease spread, and the stench of burning bodies clung to the air. It was within this world of mechanized death that the girl appeared.

No one knows her name. Perhaps she was deported from Warsaw, Białystok, or Lublin. Perhaps she was the daughter of musicians, or maybe she had never sung a note before the war. What is known comes from the fragmented testimonies of survivors: a girl with pale hair, her dress tattered, who wandered close to the barbed wire fence one evening.

That day, prisoners had been ordered to drag bodies toward mass graves. Many of them were children like her, lying in silence, robbed of names and futures. The girl stopped, her eyes wide not with fear, but with something deeper—an aching recognition. She stepped closer, ignoring the shouted threats of guards. And then, in a trembling voice, she began to sing.

It was not a song of joy. It was not the cheerful tune of playgrounds or the bright melodies of folk tradition. It was a lullaby, soft and mournful, the kind a mother would sing to a restless child in the quiet of night. Her words—half-remembered, half-lost—were said to be these:

“They must not leave in silence.”

Over and over, her voice rose against the backdrop of the camp. The guards laughed at first, mocking the absurdity of a child serenading corpses. Some shouted for her to stop. But she did not. Her song wove itself into the horror, an unbearable reminder that these bodies were not waste, not numbers, not ash to be shoveled aside. They were people. They had been loved.

Prisoners nearby wept quietly. For them, the lullaby was not madness but mercy. In a place designed to erase every trace of humanity, the child’s voice became sacred.

The Holocaust was not only about killing; it was about erasure. The Nazis sought not merely to destroy the Jewish people, but to obliterate memory itself. Victims were stripped of names, possessions, histories. Families were separated. The dead were dumped into pits, burned to smoke, their existence denied even the dignity of a grave.

And yet, this child understood what the world’s most powerful killers feared most: memory.

By singing to the dead, she gave them back a fragment of their humanity. She affirmed that they had lived, that their passing mattered, that silence would not claim them utterly. Her song was resistance—not with guns or uprisings, but with compassion. It was a voice saying: you are not forgotten.

The story does not tell us what became of her. Some say she was beaten and dragged away, never seen again. Others believe she was loaded onto a transport toward the gas chambers, her song silenced within minutes. Perhaps she died that very night, or perhaps she lingered a few more days, a ghost of melody wandering among the barracks.

What matters is that prisoners remembered. Long after her disappearance, they whispered her words: “They must not leave in silence.” In the months to come, when Treblinka erupted in revolt in August 1943, some claimed they still heard her voice, urging them on—not in rage, but in remembrance.

Holocaust memorials today often emphasize numbers: six million Jews, 900,000 at Treblinka, 1.1 million at Auschwitz. But numbers cannot capture the singular life of a child who sang. Her story reminds us that the Holocaust was not only the destruction of communities, but of individuals with dreams, fears, and songs.

Modern historians speak of “cultural resistance” during the Holocaust—the quiet ways prisoners defied annihilation by preserving humanity. Secret schools in ghettos. Hidden prayer services in barracks. Smuggled diaries. And sometimes, the voice of a child.

This girl’s lullaby belongs to that tradition. It was not merely a song; it was history written in melody, a record carved into the memory of those who heard it. And through them, it reached us.

Eighty years later, why does the story of a nameless child still resonate? Because it pierces through abstraction. We read about genocide and risk numbness; statistics blur, atrocities pile upon each other until they lose shape. But one child, singing to the dead, cannot be ignored.

Her lullaby forces us to confront what was lost—not in millions, but in one. One voice. One life. One song. And through that, she restores meaning to the masses who perished in silence.

In today’s digital world, where memory is fragile and misinformation spreads, her story calls us to vigilance. Holocaust denial remains a persistent threat. But against denial, we have the undeniable truth of survivors’ testimonies. We have stories like hers—fragile, but enduring.

In combining these themes, her story becomes not just a tale of the past but a guide for the present.

Somewhere in the ruins of Treblinka, where grass now grows over mass graves, the silence is deafening. Visitors come, lay stones, whisper prayers. No voices remain. And yet, if one listens carefully, imagination supplies what history remembers: a child’s voice, fragile but insistent, singing to the dead.

She sang because they must not leave in silence.

And today, we remember because her song still calls to us—urging us never to forget, never to turn away, and never to allow silence to fall where voices once lived.

The Holocaust was an abyss. Yet even in that abyss, there were sparks of humanity—fleeting, fragile, but indestructible. The story of The Girl Who Sang to the Dead is one of those sparks. A child’s lullaby became a weapon against erasure, a thread of memory that binds us across generations.

When we speak of Treblinka, we must not speak only of death. We must speak also of her voice, because in remembering her, we remember them all.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.