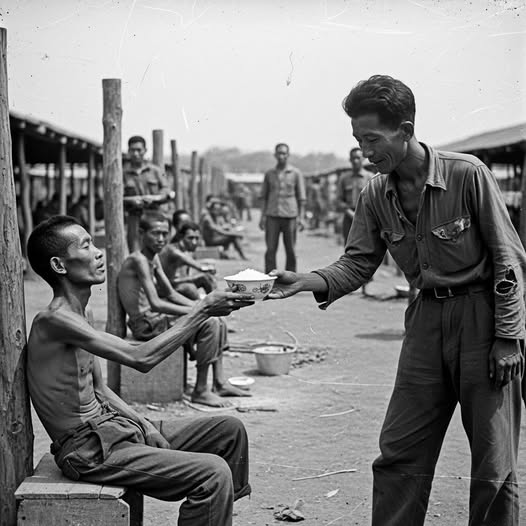

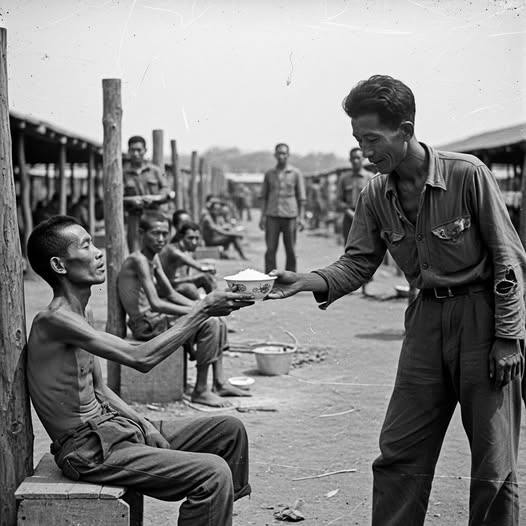

A prisoner of war who surrendered his rations – Burma, 1943

Burma, 1943. The jungle was unforgiving—the air thick with humidity, saturated with the smell of rotting leaves and the sweat of men whose lives had been reduced to a single goal: surviving another day in a Japanese labor camp. Allied prisoners of war, exhausted by the tropical climate, disease, and starvation, labored to build the Burma-Siam Railway—later known as the “Death Railway.” For each of them, a bowl of rice was everything: their only hope of survival, the currency of life and death.

Among the hundreds of emaciated figures, there was one man whose face would be forever remembered. He was as emaciated as the others—skin stretched taut over his bones, eyes sunken, hands trembling with exhaustion. Yet there was something about him that set him apart from the rest: a remnant of tenderness toward others, a remnant of humanity that the war had tried to rob. One day, as the sun beat down on the camp and the prisoners slowly returned from work to their barracks, he noticed his companion stumbling, losing consciousness. Hunger sapped his strength, and every step became a struggle.

In the evening, when rations were distributed—a small portion of rice, supposed to last the entire day—the emaciated prisoner didn’t hesitate for a moment. He handed his bowl to his friend, gently moving it. “Your wife is waiting for you. Eat,” he said quietly, as calmly as if the offering were natural. For him, that portion of rice could mean another day of life. By handing it over, he signed his own death warrant.

The next day, his bunk was empty. He didn’t survive. But the one to whom he had given his life did. Returning home after the war, he carried in his heart the memory of a man who, in the midst of the hell of World War II in Asia, chose altruism over survival. Every year, on the anniversary of the camp’s liberation, he prepared a bowl of rice and placed it on the table. Not for himself. Not for his family. For a friend whose name others might not remember, but whose gesture saved an entire future. Because thanks to him, he returned, married, raised three children, and was able to tell his story to future generations.

The story of the construction of the Burma-Siam Railway, built by the Japanese army in 1942–1943, is one of the darkest chapters of World War II on the Asian front. Over 60,000 Allied prisoners of war and approximately 200,000 Asian laborers (so-called romusha ) were forced to work in inhumane conditions. Tropical diseases—malaria, dysentery, and beriberi—took a terrible toll. The mortality rate among the prisoners was around 20%, and among the Asian laborers it was even higher. Beatings, malnutrition, and lack of medical care were commonplace.

In this world, where a person’s life weighed less than a dozen grains of rice, every act of solidarity was a miracle. The story of the prisoner who surrendered his food rations became a symbol of how, even in a place where brutality and death prevailed, traces of humanity still existed.

For the survivor, that bowl of rice held more meaning than all his medals and decorations. It was a reminder that he owed his life to someone who never saw the end of the war. That’s why, as his children grew up, he spoke not only of suffering but also of that single moment of kindness. He taught them that the history of World War II in Asia was not just about Japanese brutality, Japanese labor camps, or the hell of Burma, but also about acts of solidarity, acts of survivors that were more powerful than terror.

Today, looking at photos from that period—the emaciated figures of prisoners, their empty stares, the barracks stretching into infinity—it’s easy to forget that each of these people had their own lives, families, and dreams. But the story of this single gesture reminds us that war, though dehumanizing, could not completely erase the capacity for love and sacrifice.

Burma in 1943 is not just a railway line through the jungle; it’s also the line between selfishness and altruism, between death and life. A POW who gave up his rice ration shifted this line so that one life could blossom anew.